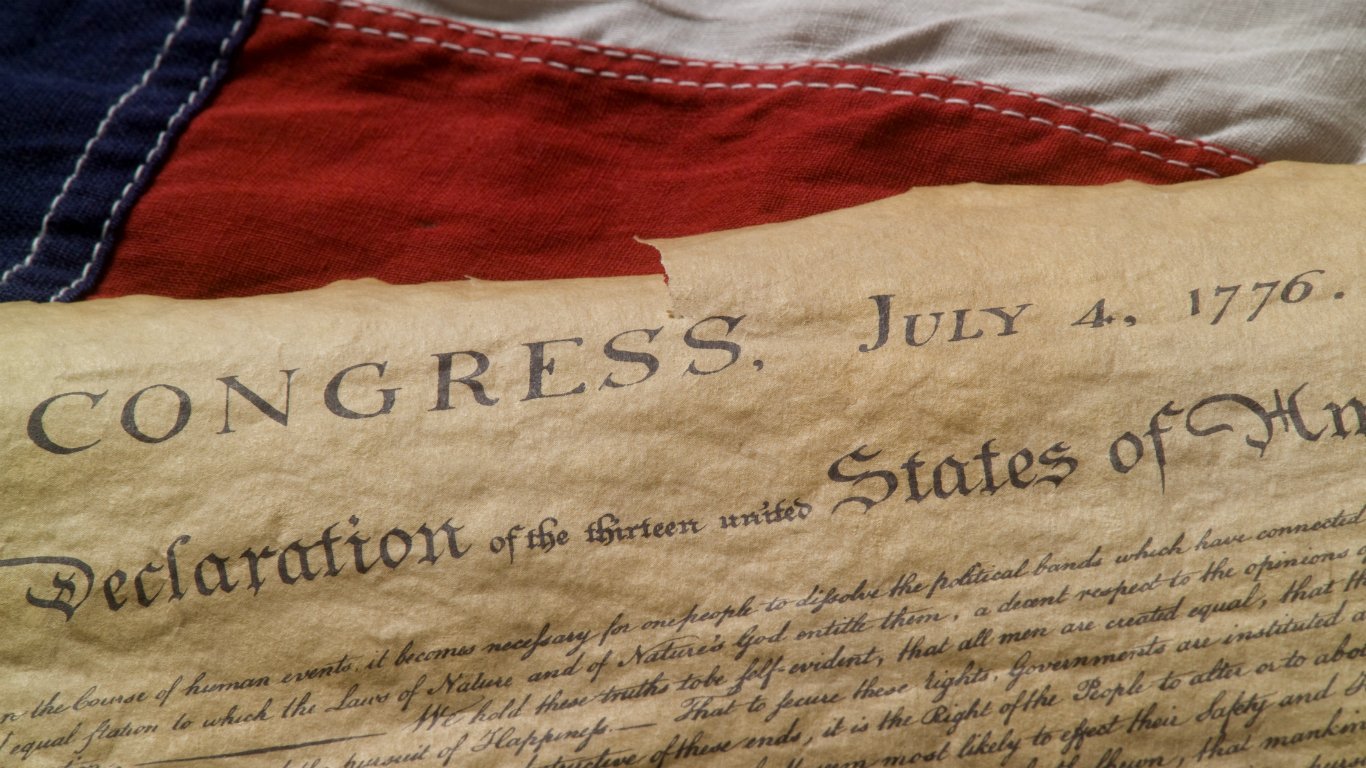

The Declaration of Independence is a signed engraving on parchment, displayed at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

Or is it?

The truth is that there are countless versions of this historic document, and almost every one is slightly different from the others in punctuation, capitalization, and minor errors.

The original rough draft of the Declaration, hand-written by Thomas Jefferson, is at the Library of Congress. According to the Harvard University Declaration Resources Project, that institution also has fragments of what was apparently the earliest draft of the document.

After a final reworking of the text, Jefferson sent cleaned-up copies to two Virginia delegates to the Continental Congress who missed the vote on the Declaration but signed it nonetheless. There’s another draft written by John Adams, and one with notes that Jefferson copied for James Madison.

Then there are various printed versions, beginning with an official broadside — a large piece of paper printed on only one side — produced by Philadelphia printer John Dunlap on the night of July 4th, 1776. A local newspaper printed the first unofficial copy on July 6th. After that, reprintings proliferated, both as broadsides and as front-page stories in some of the nation’s oldest newspapers.

Contrary to popular belief, there were no signatures at all on the July 4th version of the Declaration — only the printed name of John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress. And, with that exception, none of the early versions of the document included either the signatures or the names of the 56 people who ultimately signed the Declaration of Independence.

The familiar signed parchment version was completed on August 2nd. Many of the signers penned their names at the bottom that day, while almost all the others added theirs over the next few months. (One signer, Thomas McKean, was a slowpoke; all that’s known for sure is that he signed it sometime between 1777 and 1781.)

Despite any minor differences between all these and other iterations of the Declaration, they are all identical in sentiment, declaring the colonies to be free from British rule and establishing a new nation, the United States of America, on the principle that life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness are unalienable rights. And that’s what really matters.

The first printed version to include all the names (except for that of the laggardly McKean) appeared in early 1777, the work of Baltimore postmaster Mary Katharine Goddard, the first female postamer in the United States — one of several amazingly cool women’s firsts in history.