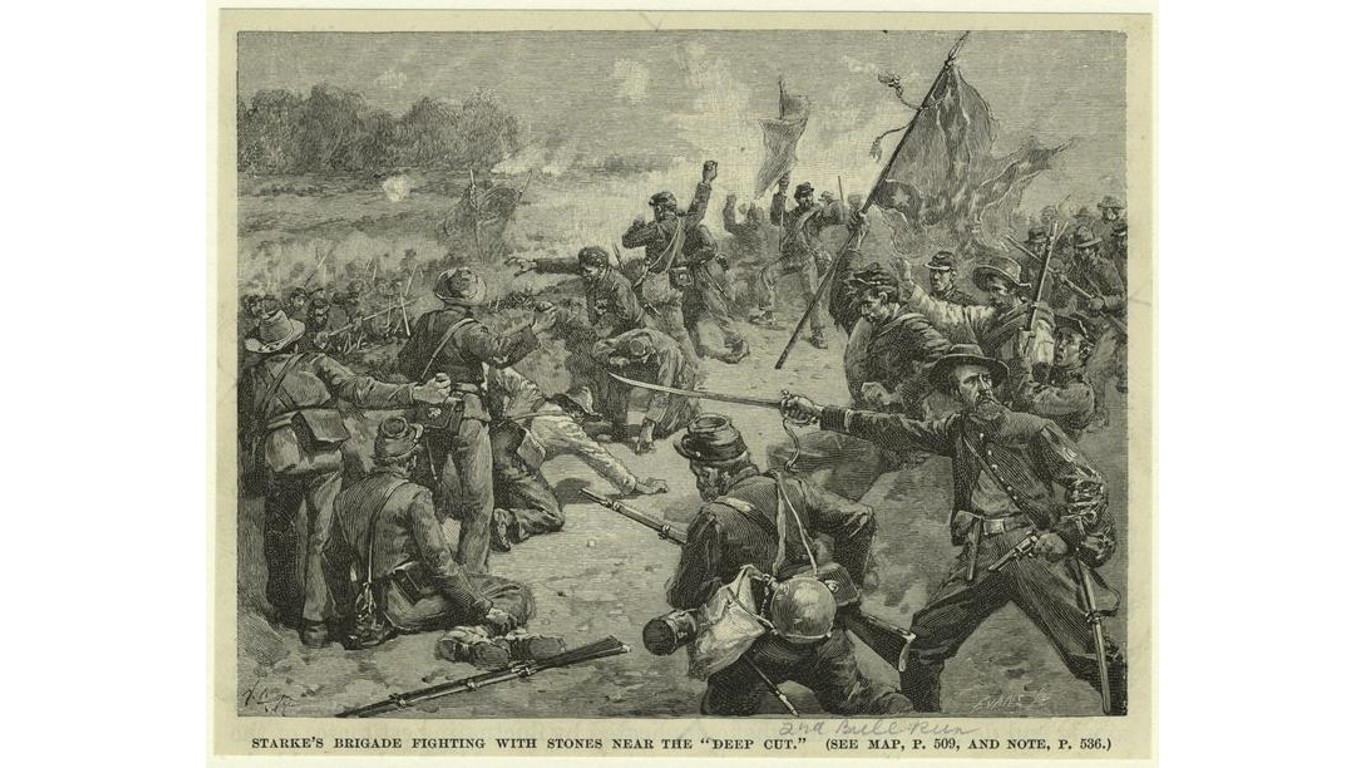

The American Civil War, which tore our country asunder from 1861 through 1865, was the deadliest conflict in our history. While exact figures are difficult to come by, it is estimated that almost 500,000 combatants, both Union and Confederate soldiers, lost their lives during the war — roughly 100,000 more than died during World War II, even though the latter was waged with far more efficient and deadlier weaponry.

Perhaps even more shocking than the total number of deaths is the fact that somewhere between half and two-thirds of the fatalities were not due to battle wounds, but to infection and disease in hospitals and prison camps.

Gastrointestinal conditions — diarrhea and dysentery — were particularly widespread and fatal. Pneumonia, malaria, yellow fever, scarlet fever, measles, smallpox, bronchitis, typhoid, and even scurvy (the result of severe vitamin C deficiency) also claimed lives.

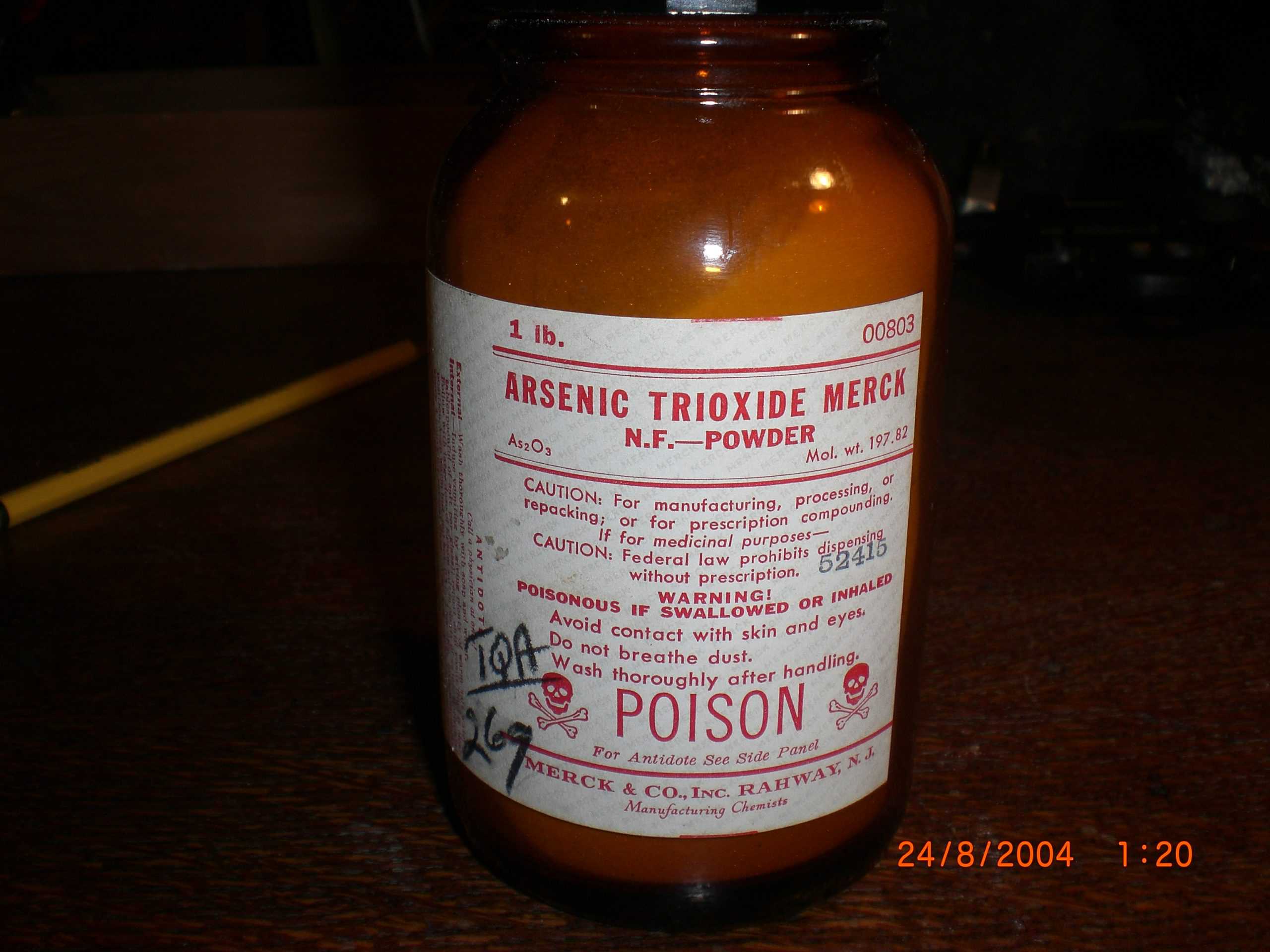

There were plenty of doctors, surgeons, and nurses on both sides, but by modern standards, their actions seem almost medieval. Bleeding and the application of leeches were still believed to be curative. Deadly arsenic and mercury were administered as medicines. The idea of germs capable of spreading disease and infection was vaguely known but not widely accepted.

On the other hand, according to a 2016 paper from Baylor University Medical Center, published by the National Institutes of Health’s National Library of Medicine, “Many misconceptions exist regarding the quality of care during the war.” The paper continues “It is commonly believed that surgery was often done without anesthesia, that many unnecessary amputations were done, and that care was not state of the art for the times. None of these assertions is true.” (We have other misconceptions about the period. Here are 10 myths about the American Civil War.)

In order to determine what Civil War medicine was really like, 24/7 Tempo reviewed the Baylor paper (“Medical and surgical care during the American Civil War, 1861–1865” by Robert F. Reilly, MD) and other National Library of Medicine publications, as well as articles and papers on the subject from the American Battlefield Trust, the American Museum of Civil War Medicine, and the National Park Service.

As the NPS puts it, “The story of Civil War medicine is a complex one.” Here, though, are 15 things we know about it.

Germs weren’t understood

9th May 1946: In a petri dish the original growth of pencillium from which the antibacterial agent, penicillin was obtained. (Photo by Douglas Miller/Keystone Features/Getty Images)

While some basic forms of the germ theory of disease date back to the 16th century, medical professionals did not know of or widely accept the idea until the late 19th century — too late for victims of the Civil War, whose doctors were largely ignorant of the need for sterile instruments and antiseptics.

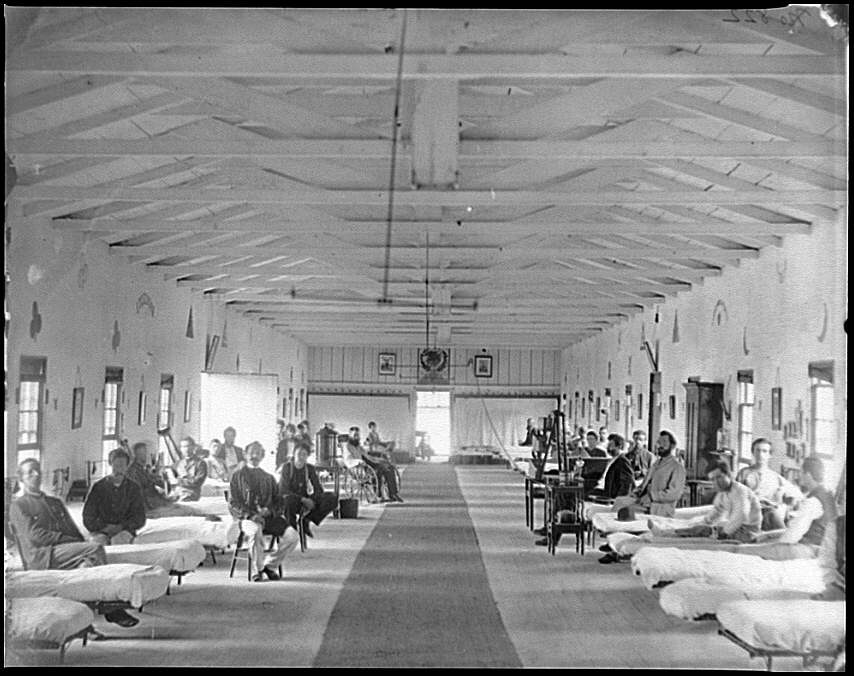

Both sides were unprepared

Neither the Confederates nor the Union side anticipated how bloody the war would be or how long it would last, so neither side had put in place systems for the care of the wounded on a large scale. The situation improved as the war raged on, but medical facilities remained limited.

Chloroform was a widely used anesthetic

injecting injection vaccine vaccination medicine flu man doctor insulin health drug influenza concept - stock image

While amputations and other surgery may have been performed in some emergency situations without anesthesia, chloroform and to a lesser extent ether were typically used to deaden the senses of patients while surgeons did their work.

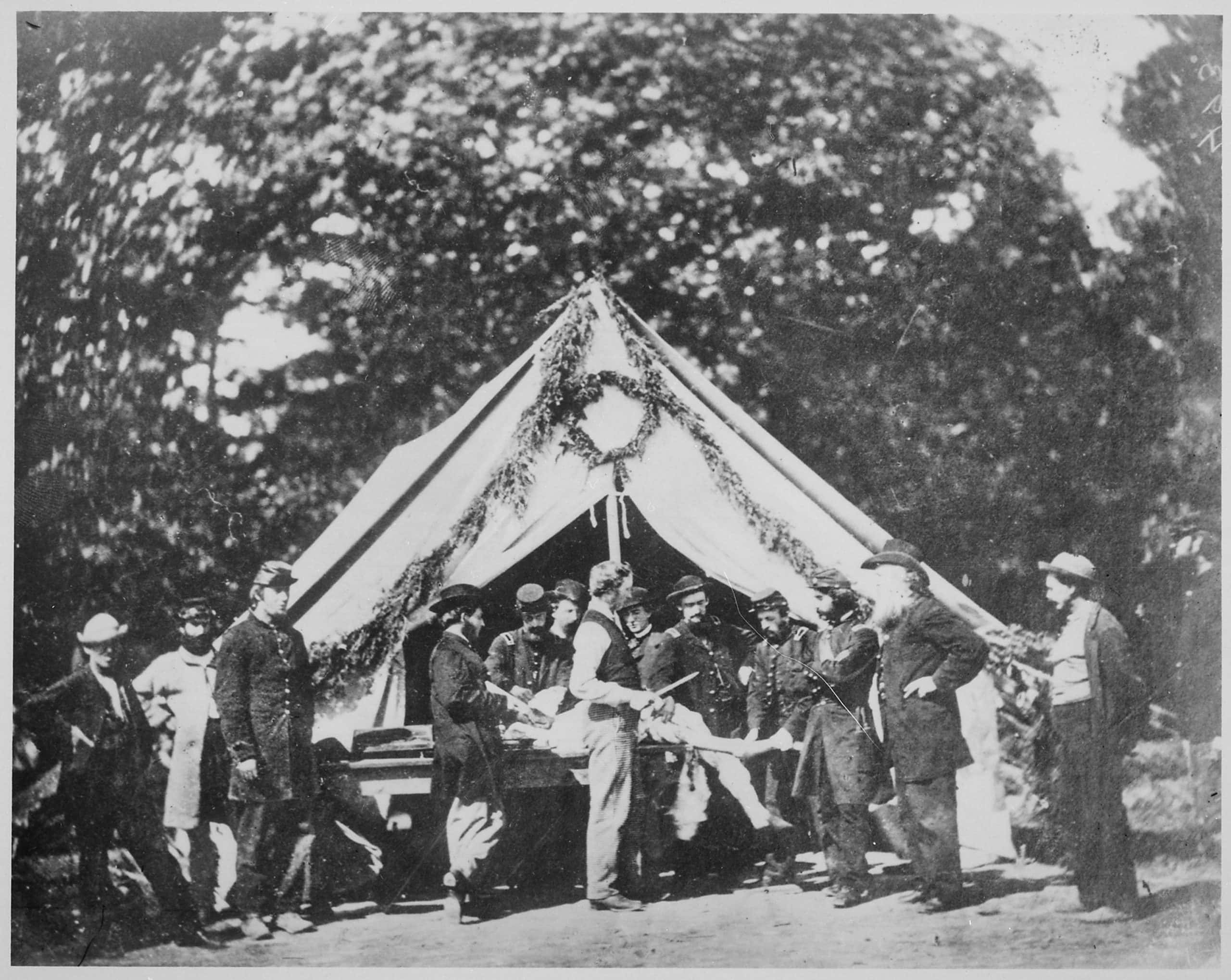

A quarter of amputees died

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/736921

Amputation accounted for about three-quarters of all surgeries performed in the course of the war, and some 26.3% of all amputees succumbed during or after the procedure, often from gangrene that set in due to the lack of sterile equipment.

Doctors made an important discovery

One thing that became apparent to surgeons partway through the war was that time was of the essence in performing amputations. Patients who were operated on within 24 hours of their wounding, it was learned, stood a higher chance of survival than those who had to wait 48 hours or more.

Only the most skilled could amputate

Not just any doctor could perform amputations. It was considered a job for the most experienced among them, and it is said that on the Union side, at any rate, only one doctor in 15 was given permission to amputate.

Post-operative infection was a major problem

Nurse doing hand hygiene to prevent Coronavirus infection.

Whether after amputation or some lesser surgery, patients were highly susceptible to infection, given the lack of knowledge about germs. The most effective treatment used was a chemical element called bromine, which also had a sedative effect. (It is sometimes used today as an alternative to chlorine in swimming pools).

Morphine and whiskey were often prescribed

When the goal was to deaden or lessen pain outside of surgery, the preferred anesthetics were morphine, extracted from the resin of the opium poppy and widely prescribed as a pain-killer in the 1800s, and whiskey, which would have been Bourbon (General Ulysses S. Grant was a fan of Old Crow, a brand that’s still sold) or in some cases Irish — the influence of immigrants driven to the Northern states from Ireland by the potato famine.

Quinine was used against malaria

Macro Photo of Yellow Fever, Malaria or Zika Virus Infection - Mosquito Insect on Leaf

Quinine, extracted from the bark of the cinchona tree, was being used as a treatment for malaria as early as the 1600s. During the Civil War, some troops took it as a preventative measure, but it was also prescribed to help lessen the disease’s effects once it took hold. Supply chain issues made it difficult for the Confederate side to obtain quinine, and doctors sought alternatives, including extracts from willow and dogwood trees, which were only marginally effective.

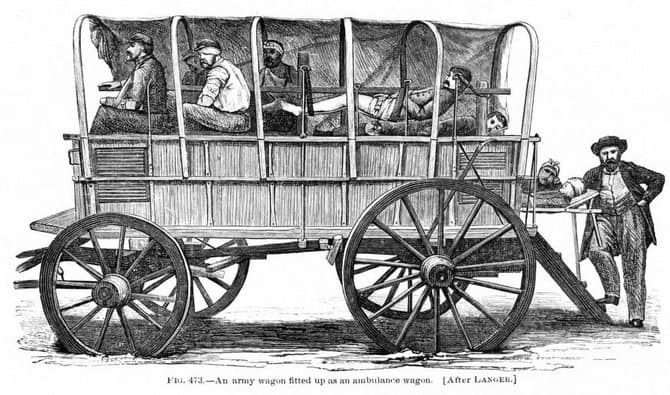

Field ambulances were developed

When the war broke out, there were no military ambulances, so civilians were pressed into service to drive the wounded to hospitals. This didn’t work out well, as the civilians tended to desert, and soldiers who had not been wounded sometimes commandeered the vehicles to escape battle. In August of 1862, however, the Union Army established an ambulance corps under the direction of the Quartermaster, and ambulances run by the military have existed ever since.

Mercury and arsenic were considered medicines

Mercury, now known to be toxic, was used to treat syphilis and other diseases, and calomel (mercurous chloride) was considered a cure for diarrhea. A medicine called Fowler’s Solution, which contained arsenic, was thought to reduce fever.

Plastic surgery was pioneered

A Union soldier, Pvt. Carleton Burgan, was given mercury-containing calomel as a treatment for pneumonia. The substance caused a large ulcer extending from his eye to his upper lip, disfiguring him. Dr. Gurdon Buck, considered the father of plastic surgery in America, operated on him, reconstructing his face. This is considered one of the first successful examples of plastic surgery in the country.

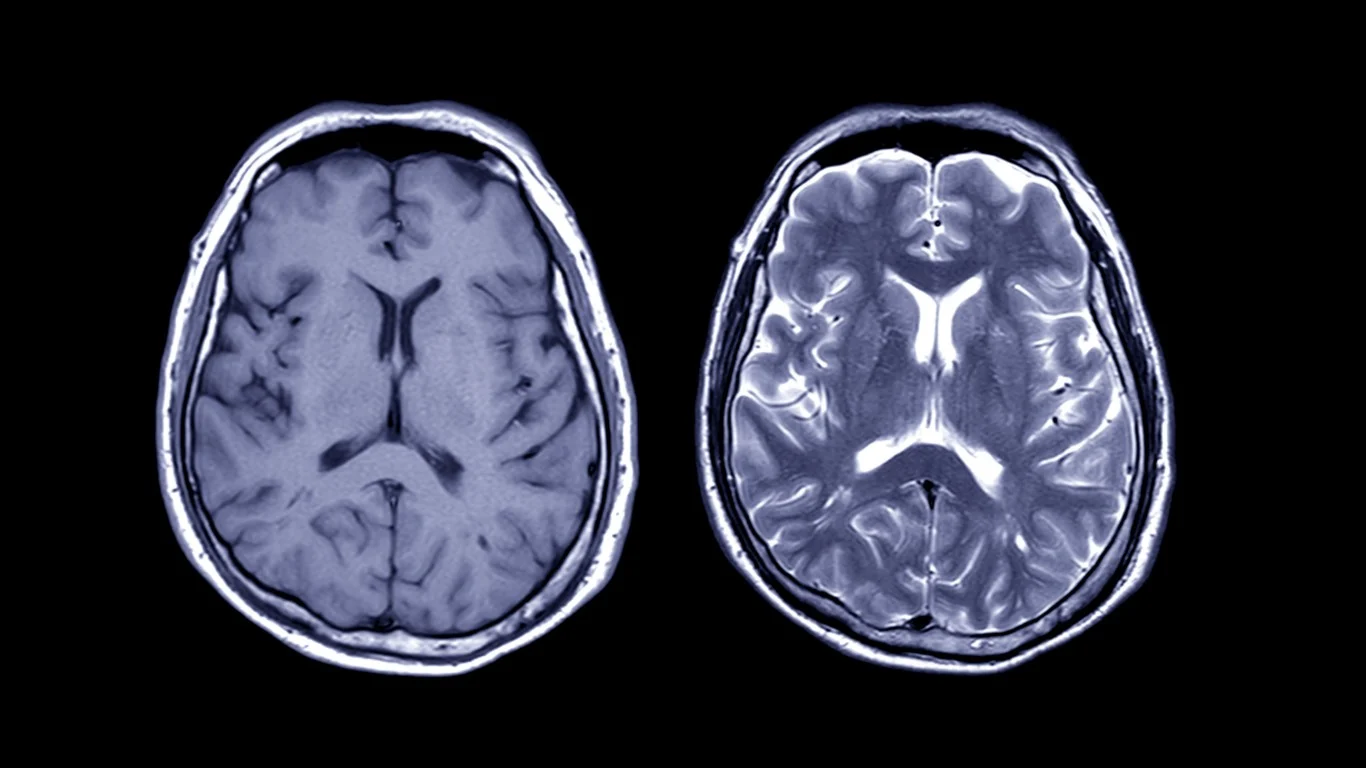

Doctors performed brain surgery

Surgeons during the Civil War knew a surprising amount about head injuries, and there were written instructions informing doctors how to deal with gunshot wounds, puncture wounds, and blunt force trauma. Sections of the skull were often removed to allow access to wounded areas. One key figure in head surgery during the war was Maj. William Williams Keen Jr., who has been called “America’s first brain surgeon.”

Clara Barton had lasting importance

Massachusetts-born self-taught nurse Clara Barton, who would later found the American Red Cross, worked tirelessly throughout the war to minister to both Confederate and Union wounded (including Black soldiers) and to help supply food, clothing, and medical necessities to troops at the front. In charge of battlefront hospitals for the Army of the James late in the war and supervisor of the Office of Missing Soldiers after the war, Barton is credited with proving that women could function well in high-stress situations, and with being an early supporter of civil rights. She “took the initiative to manage emergencies and jump into action during times of crisis,” according to Nurse Journal, and “Her impact is felt in nursing and healthcare to this day.”

Modern medicine owes much to the era

Forced to adapt to conditions that would have been previously unimaginable, doctors and other medical professionals during the Civil War made great strides in patient care, given the limitations of the period. “As doctors and nurses became widely familiar with prevention and treatment of infectious diseases, anesthetics, and best surgical practices, medicine was catapulted into the modern era of quality care,” according to an article by Ina Dixon entitled “Civil War Medicine: Modern Medicine’s Civil War Legacy,” published by the American Battlefield Trust. She concludes “Many of America’s modern medical accomplishments have their roots in the legacy of America’s defining war.” (See what a hospital looked like 100 years ago.)