Many misconceptions about the American Civil War pervade our current knowledge.

Some myths about the Civil War are relatively harmless, albeit slightly strange. Still, some of the misinformation regarding the conflict harms our ability to learn from the actions of our ancestors. As we move forward from the violence of the Civil War, it’s essential to identify and dispel harmful myths about our history that prevent us from moving forward and creating a more equitable future for all people. Let’s examine some of the most prominent myths about the Civil War, ranging from the harmless and strange to more pervasive and harmful ones.

For this list, we started by determining the most pervasive myths about the Civil War. We consulted other published lists and online discussions to see which misconceptions were most common. Once we identified the most prevalent myths about the Civil War, we began researching the truth behind those misconceptions. We consulted as many primary sources as possible, secondary sources, and scholarly opinions from historians and professors who studied the Civil War. We made an effort to focus on primary sources where we could.

However, the destruction of Confederate documentation after the war makes it difficult to paint a complete picture of the Confederacy from primary sources alone. Thus, we had to use many primary sources from the Union regarding the Confederacy, which we acknowledge may contain an unconscious (or conscious) bias. (Also Read: This Is the State With the Most Civil War Deaths: All States, Ranked)

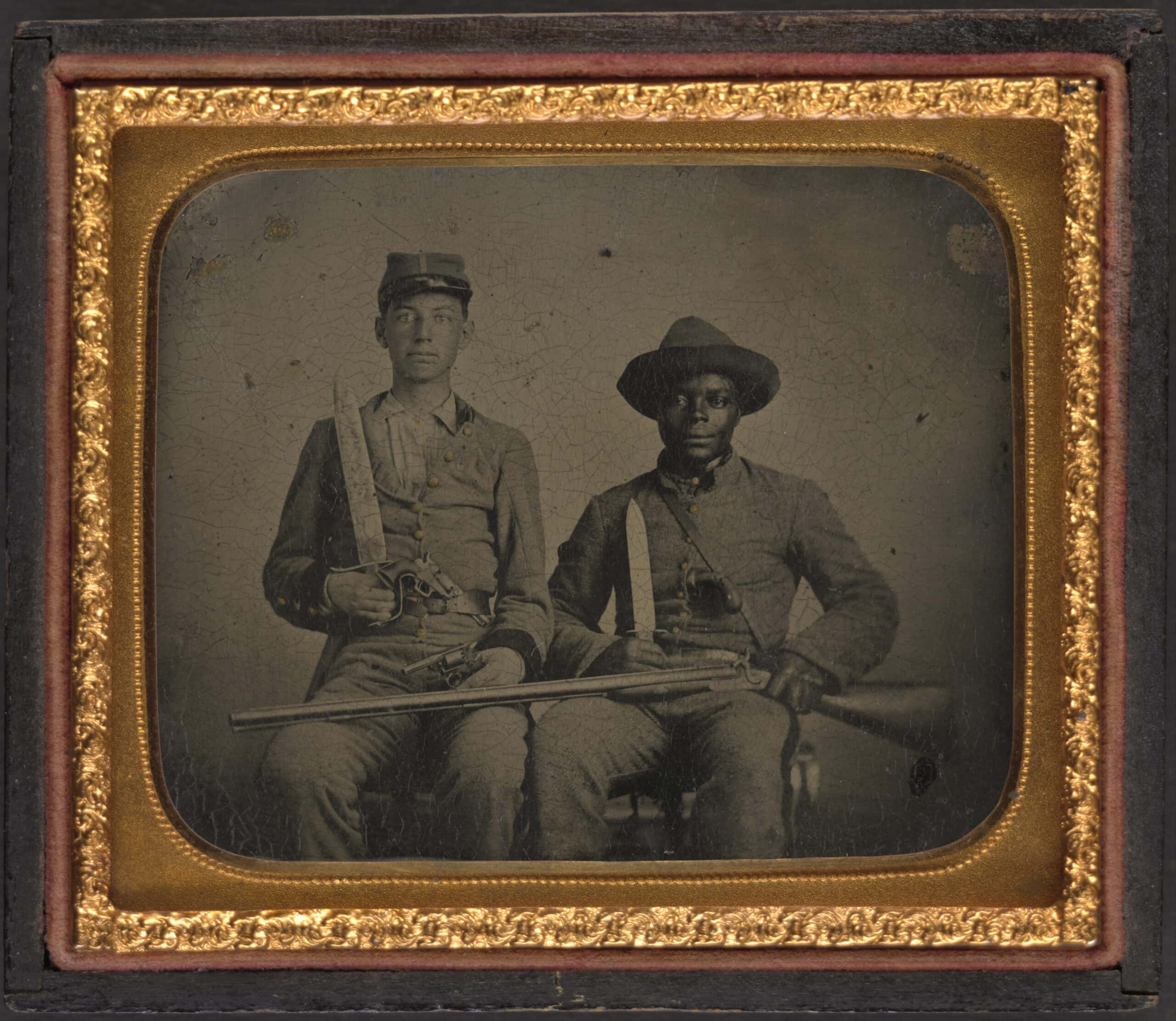

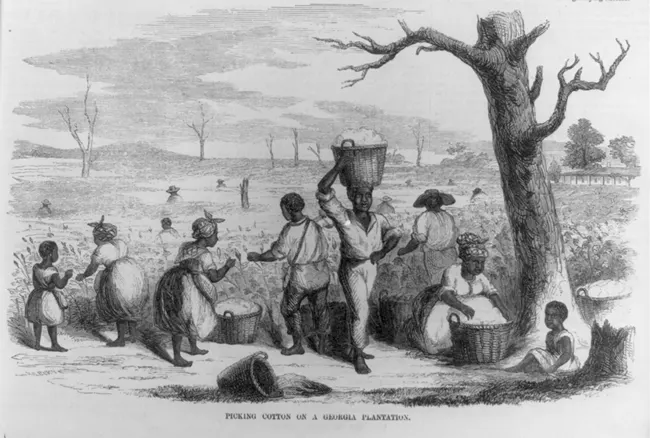

Black people, both free and enslaved, fought for the Confederacy

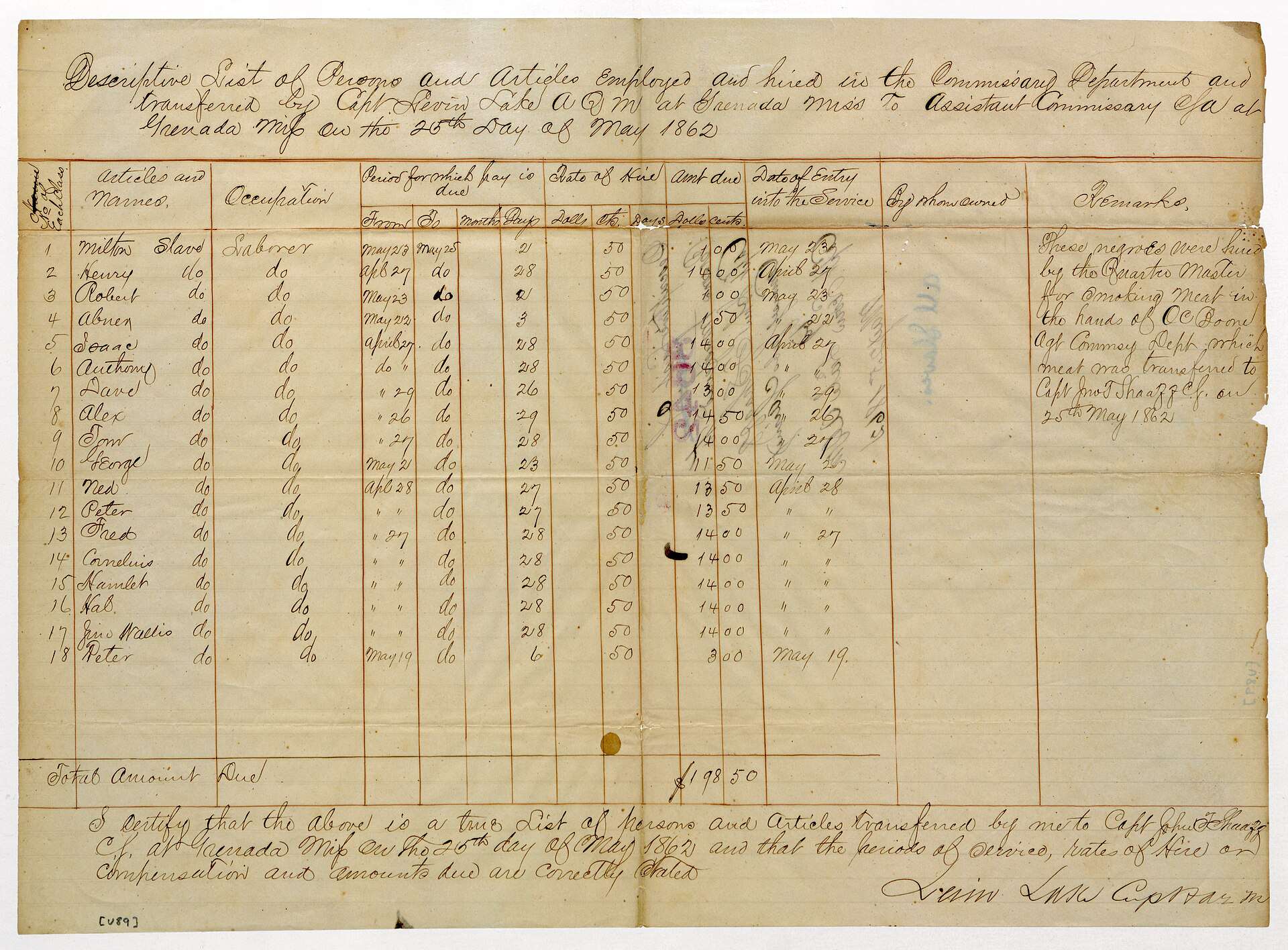

Some people continue to disseminate the very harmful myth that Black folks, free and enslaved, fought on the side of the Confederacy. The first tidbit that should indicate that this factoid is patently false is that the Confederacy didn’t allow Black people to enlist until 1865, three months before the Confederates surrendered. The topic had been up for debate for quite some time, and leaders didn’t push it forward until there was no other choice. The Confederacy did not want to allow Black people, especially enslaved ones, to enlist in the army as this essentially set them free. There was no realistic way to send them back to the plantations after they’d fought in the war.

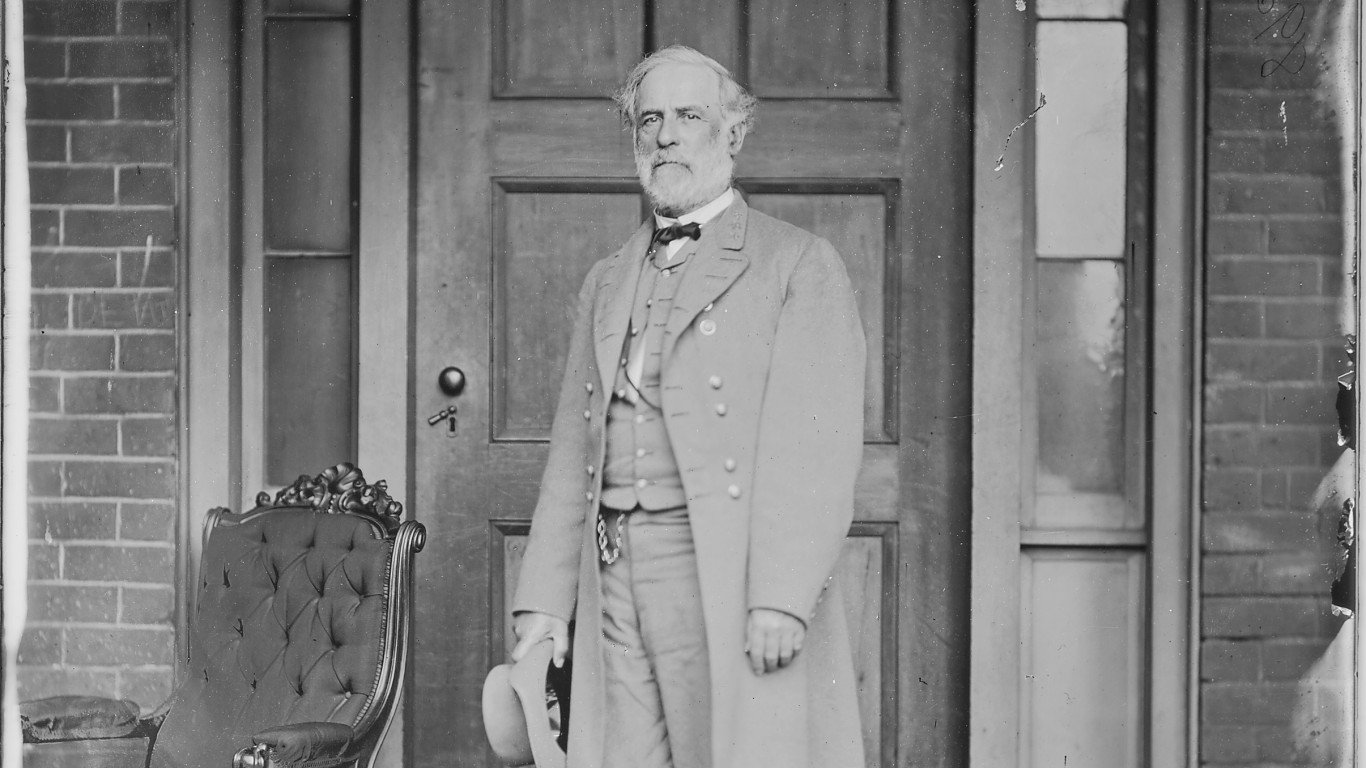

There were many opinions about whether slaves should be allowed to serve in the army and what would happen to them afterward. “What did we go to war for, if not to protect our property?” and “If slaves will make good soldiers, our whole theory of slavery is wrong.” were real, expressed opinions from Southern politicians. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee opined, “We must decide whether slavery will be extinguished by our enemies and the slaves used against us, or to use them ourselves.” While he did ask that slaves who served become free men following their service, this was not included in the 1865 Confederate bill that allowed Black people to serve.

Truth: Black men were enlisted

These things considered, it’s easy to debunk the idea that Black men in the South were actively taking up arms to protect the Confederacy. Following the passing of the bill allowing Black soldiers in the Confederate army, several thousand Black men were enlisted (not all by choice). However, that did not prevent the eventual fall of the Confederacy.

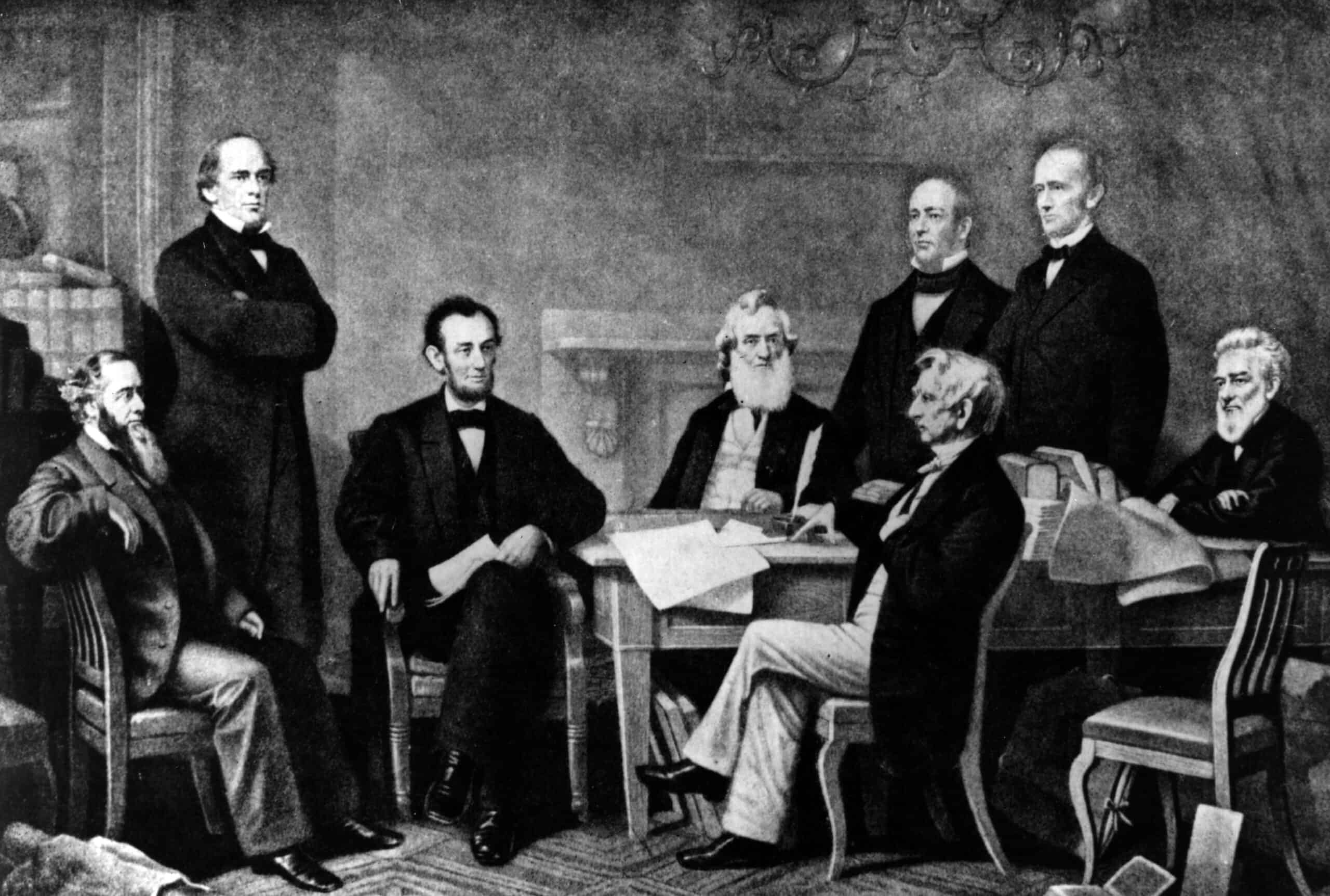

The Union went to war to end slavery

Many schools teach that the reason the Union went to war against the Confederacy was to end slavery in America. While the abolitionist movement was certainly more prominent in the Union than in the Confederacy, the reason the federal government went to war was not to end slavery. The Union went to war to keep the Union together as a single nation. No more, no less. There wasn’t some grand plan to free the slaves in the South via war. The ultimate goal was merely to keep the Union whole, not to abolish slavery.

In President Abraham Lincoln’s first inaugural address, he stated the following: “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” So, while we know that Lincoln himself opposed slavery, he didn’t go into the war thinking that he was going to abolish and free the slaves. However, abolitionism among the Union army grew exponentially during the Civil War as many escaped slaves flocked to the soldiers seeking refuge and assistance.

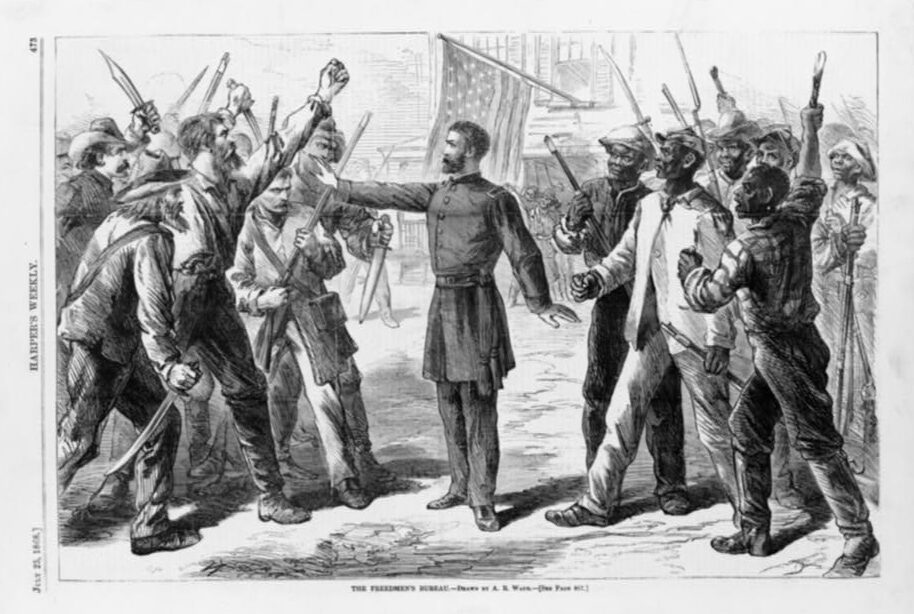

Truth: The Emancipation Proclamation kept the institution of slavery intact in some states

The rise of abolitionism as a policy within the Union didn’t start until the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and even that bill kept the institution of slavery intact within border states that had not seceded. So, it’s pretty easy to see that abolitionism was not the goal of the Civil War from the Union’s perspective. Lincoln was very clear that he would do what he could to appease the Southern states as long as the United States was kept whole.

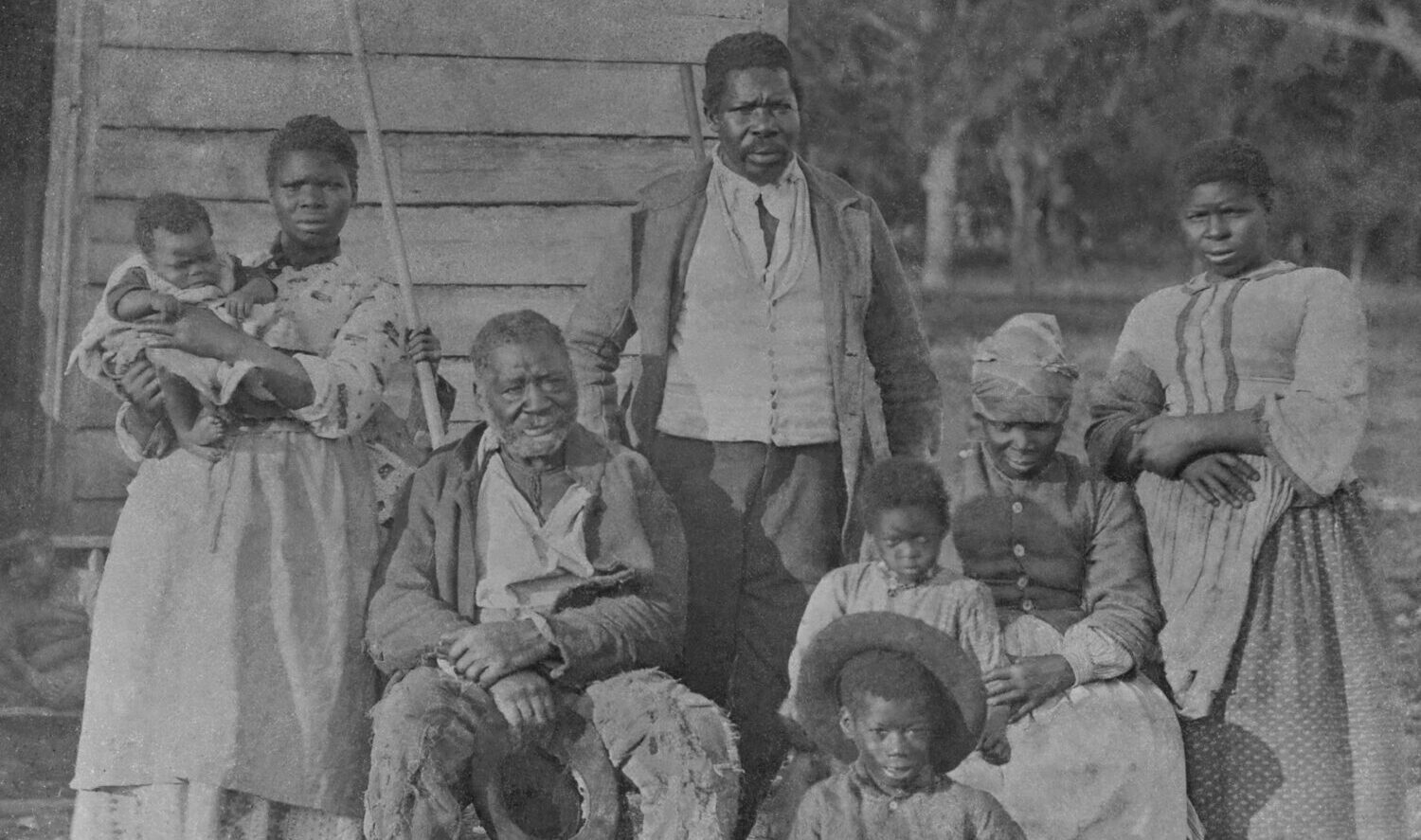

The Civil War wasn’t about slavery

Every time someone says, “The Civil War wasn’t about slavery,” an angel loses its wings. Many, many teachers, especially in the South, teach their students that the South didn’t secede because of slavery but because of states’ rights. Some estimates indicate that somewhere between 60% and 75% of United States teachers genuinely believe that the South’s motivation to secede was solely states’ rights. However, surviving documentation from Confederate leaders does not support this. Confederate leaders were very clear that they were going to war because they did not want slavery to end. Even a simple cursory look at statements made by Southern politicians and leaders indicates that the driving force of the war effort was to retain possession of their slaves.

The State of Mississippi released the following statement surrounding its support of the Civil War: “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery — the greatest material interest of the world.” They end their statement with a simple “a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization.” The State of Texas declared: “We hold as undeniable truths that the governments of the various States, and of the confederacy itself, were established exclusively by the white race, for themselves and their posterity; that the African race had no agency in their establishment; that they were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race, and in that condition only could their existence in this country be rendered beneficial or tolerable.”

Truth: It was not about state’s right

States throughout the South held and expressed similar positions during the war. So, it is impossible to disentangle the institution of slavery from the Civil War. Essentially, if you think it was about states’ rights, you’re wrong. The very people who declared what the war was about said it was about slavery.

The pre-Civil War era was the low point of American race relations

Many people also erroneously believe that race relations in the United States were only a positive trend following the Civil War, and pre-Civil War America was the lowest point of interracial relations. However, it would be patently false to say that race relations never hit another low or that they were always on an upward trend after the Civil War.

U.S. historians point to the absolute low point of American race relations as being the period between 1890 and 1940, just after the Civil War. During this time, racism was not unique to the South; the North engaged just as much casual and aggressive racism as the South. From segregation to eugenics, racism flourished during this time. A few Black athletes faced serious and dangerous racism when attempting to take their careers into the professional sphere decades before Jackie Robinson joined Major League Baseball. During this period, many areas had sundown towns where Black people were officially or unofficially barred from entry.

Truth: Race relations continued to be at low point

This period of race relations in the U.S. is the driving force behind the more insidious myths about the Civil War. Many historians believe that kotowing pro-Southern Civil War myths was, at least in part, a way to smooth over the relations between the North and the South following the war. Continued talks of the war, its causes, and its effects. The idea is that continuing to talk about the conflict would cause Southerners to feel alienated from the Union as if they’d been forced to join a country that detests them. Unfortunately, this has led to a widespread belief that race relations are great, slavery is “over,” and reparations are not necessary, which is equally, if not more, harmful.

Surgeons in the Civil War performed surgery without anesthesia

Many Americans believe that Civil War-era surgeons, especially on the battlefield, performed surgeries without an anesthetic. There is a surprisingly common mental image of a Civil War surgeon as a ruthless butcher removing limbs with a hacksaw, and the only pain relief given to the soldier was a shot of whiskey and a bullet to bite down on. We are happy to announce that this is balderdash, and Civil War surgeries were not quite so brutal.

Civil War-era surgeons documented many different anesthetics used during surgeries, the most common of which is chloroform. It is not nearly as refined as the options we have today with intravenous medications, but it gets the job done. Chloroform for anesthesia was commonly available to both sides of the war. Confederate surgeons documented the use of chloroform in surgery until the end of the war, even when supplies were low. If an anesthetic were unavailable for some reason, the surgeon would typically delay the operation to ensure patient comfort.

Truth: Anesthesia was common

Comfort isn’t the only reason that Confederate and Union surgeons valued anesthesia. There are many crucial logistical reasons why a surgeon would only want to operate on a patient who is under anesthesia. For instance, even if the patient is unconscious, they’re going to move. In the modern day, we don’t just knock patients unconscious when we operate on them. We also give them large doses of muscle relaxers and preemptive pain relief so that the unconscious body doesn’t react to the surgeon’s cuts. Your body doesn’t stop feeling and responding to pain just because it’s unconscious, and if you move, you could kill yourself accidentally. So, anesthesia was just as necessary during the Civil War as it is today.

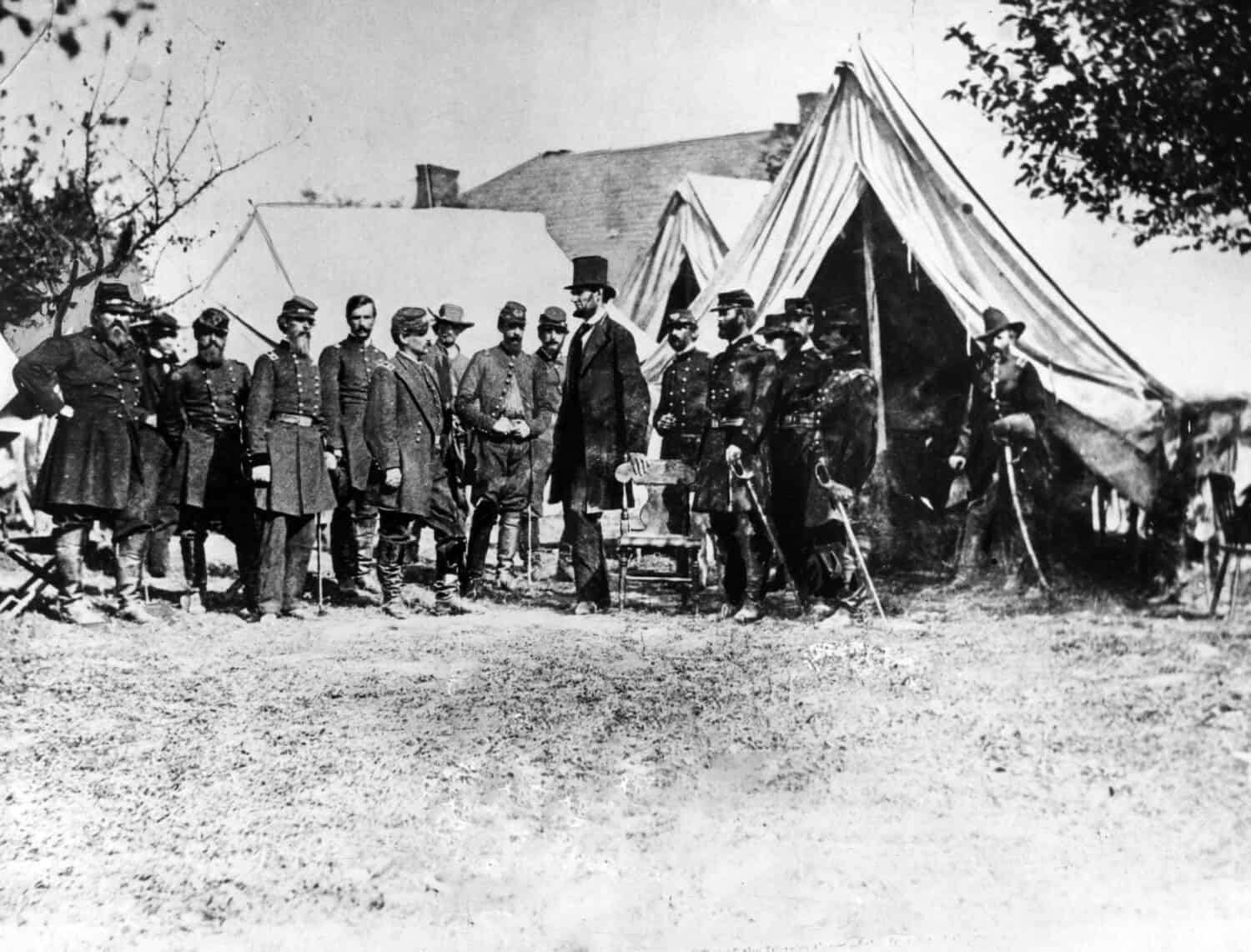

Lincoln’s policies were popular in the North

Another myth about the Civil War is that Lincoln’s policies enjoyed widespread popularity in the American North. The prescription of Lincoln as a heroic figure is primarily a lionized version of him that Americans look at in hindsight. As the general public warmed up to social justice more, the perception of Lincoln as a champion of equal rights became more common. However, many in the North considered his policies heavily divisive, which was the best the North could hope for. Lincoln himself was hardly a popular figure at the time. With four candidates on the presidential ballot, he won with just 39.8% of the vote, which remains among the lowest winning turnouts for any president ever.

The Salem Advocate, a newspaper from Lincoln’s home state of Illinois, printed a 188-word tirade about how he was a disgrace to the nation. The editor of the Massachusetts publication The Springfield Republican opined (despaired, really) that Lincoln was a “simple Susan.” Edward Everett, the most decorated public speaker in America at the time, called Lincoln “a person of very inferior cast of character.” Congressman Charles Francis Adams wrote, “His speeches have fallen like a wet blanket here. They put to flight all notions of greatness.”

Truth: Many opposed it

The Emancipation Proclamation was immensely divisive legislation, even if it had far less reach than we like to remember it having. The Kentucky government, which never officially seceded even though it did send 35,000 troops to the Confederacy, vehemently opposed the legislation. There is even evidence that there was pressure on the governor to reject the proclamation altogether.

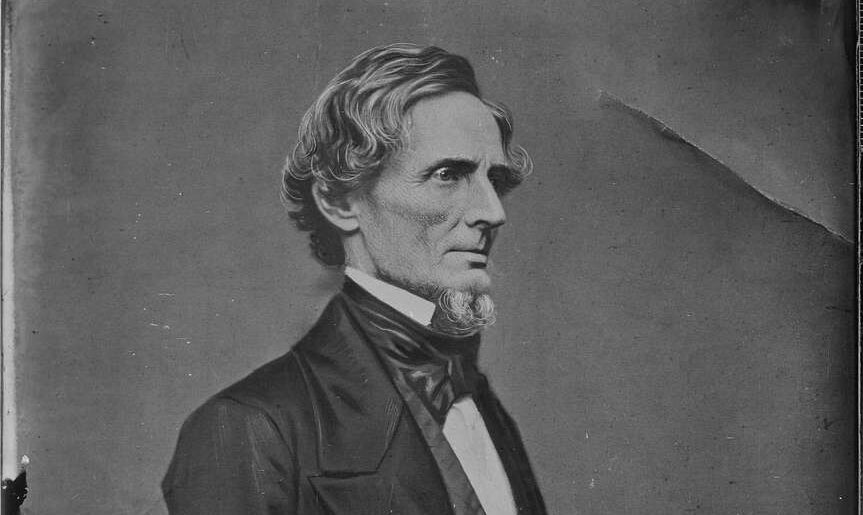

Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis were staunch secessionists

A prevalent myth is that Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis, who served as a Confederate general in the army and the Confederate president, respectively, were staunch secessionists who were chomping at the bit for the Confederacy to secede and become an independent nation. However, looking at their documentation, it doesn’t seem they favored secession over keeping the Union together. They may have personally preferred to keep the Union together and viewed secession as a last resort to protect their state’s interests.

Davis started his career as a Missouri senator who initially opposed calls for secession. The following quote from Davis exemplifies his personal views on secession from the Union: “My friends, my brethren, my countrymen…I feel an ardent desire for the success of States’ Rights Democracy…alone I rely for the preservation of the Constitution, to perpetuate the Union and to fulfill the purpose which it was ordained to establish and secure.” Davis desired a more relaxed view on states’ rights, giving them more freedom to be separate from the federal government while preserving the overall union. After all, it was the Union of the States that allowed them to become free from the influence of Great Britain. They were—and still are—more potent as a unit than separately.

Truth: Lee did not think secession was necessary

On the other hand, Lee opined, “If Virginia stands by the old Union, so will I. But if she secedes (though I do not believe in secession as a constitutional right, nor that there is sufficient cause for revolution), then I will follow my native State with my sword, and, if need be, with my life.” This quote makes his position clear: He doesn’t believe secession is necessary or even lawful.

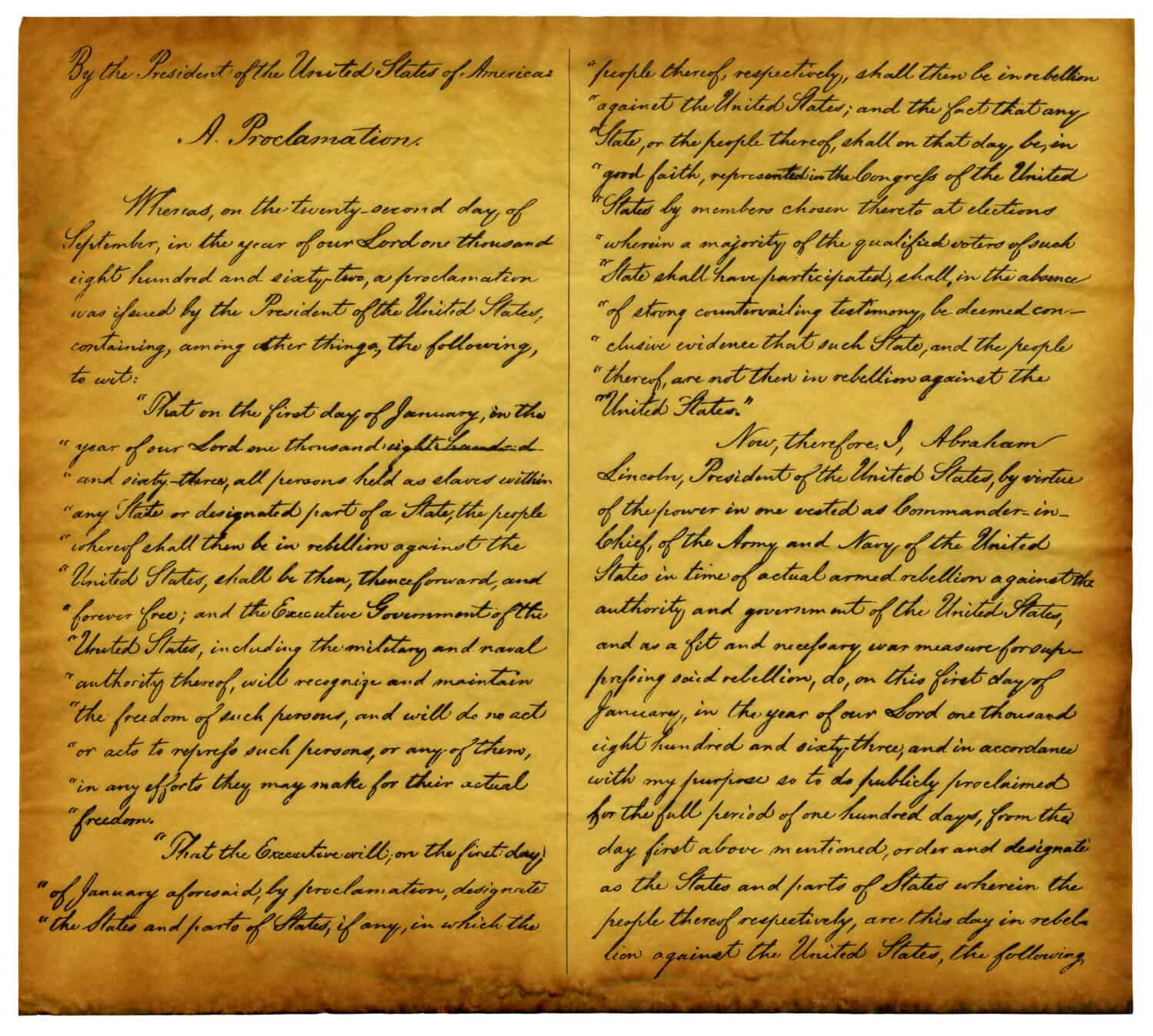

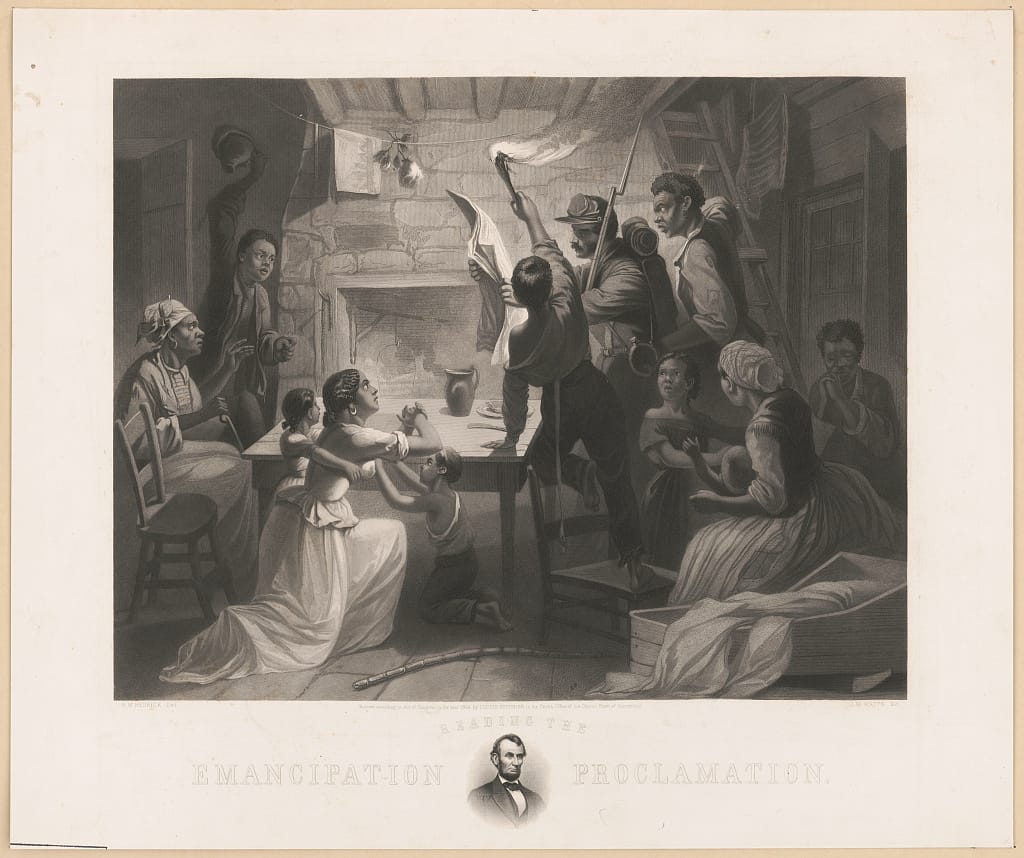

The Emancipation Proclamation ended slavery

Undoubtedly, the Emancipation Proclamation was a crucial document in the Civil War and history in general. Not only does it mark the beginning of a firm stance of abolitionism within the U.S. government, but it also changes the entire Civil War conflict from a war to preserve the Union to a war to end slavery. However, the Emancipation Proclamation was not nearly as wide-reaching despite how we often remember and teach in American schools. Though many oversimplify it this way, it most certainly did not “end slavery,” although it was the beginning of federal abolition movements.

Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation into law in late 1862, declaring that as of Jan. 1, 1863, all slaves living in states in rebellion against the Union “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” So, it only affected states that had seceded from the Union and engaged in war against it. Border states that remained loyal to the federal government were not affected and could continue to uphold slavery within their state borders if they wished (which they did). This decision is politically similar to the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which allowed Missouri to join the Union as a slaveholding state in 1821 despite protests from within Congress.

Truth: Only people in rebel states were freed

Since the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t free the entire enslaved population, not all of the 4 million men, women, children, and elderly enslaved people received fundamental human rights within the Union. Only those in rebel states received de facto freedom under the Emancipation Proclamation.

Only men fought in the Civil War

Another myth that permeates not just our knowledge of the Civil War but many other historical conflicts is that the only participants in combat were male. While this is true for the most part and something that the governments of the time endorsed and attempted to enforce, this policy didn’t stop all women from enlisting under false identities.

In 1863, a Union burial detail discovered something important and unusual: a dead woman wearing the uniform of a Confederate private. This discovery brought to light something that many people had never thought about before: the multitude of women who were engaged in the war on the frontlines. Due to the ban on women in the military at the time, it’s impossible to say precisely how many women participated on the frontlines. The army documented them under a false name or destroyed their documentation once their identity was discovered. However, current scholars believe somewhere between 400 and 750 women served between the Union and Confederate armies, fighting on the frontlines, and they largely shared the same motivations as their male compatriots.

Truth: Women enlisted, too.

Sarah Emma Edmonds, who went to war under the name Franklin Flint Thompson, said the following about her service: “I could only thank God that I was free and could go forward and work, and I was not obliged to stay at home and weep.” Albert Cashier, who was born “Jennie Hodgers,” fought for the 95th Illinois Infantry. Documents record him being present in over 40 engagements. After serving, Cashier retained his false identity and lived the rest of his life as a man.

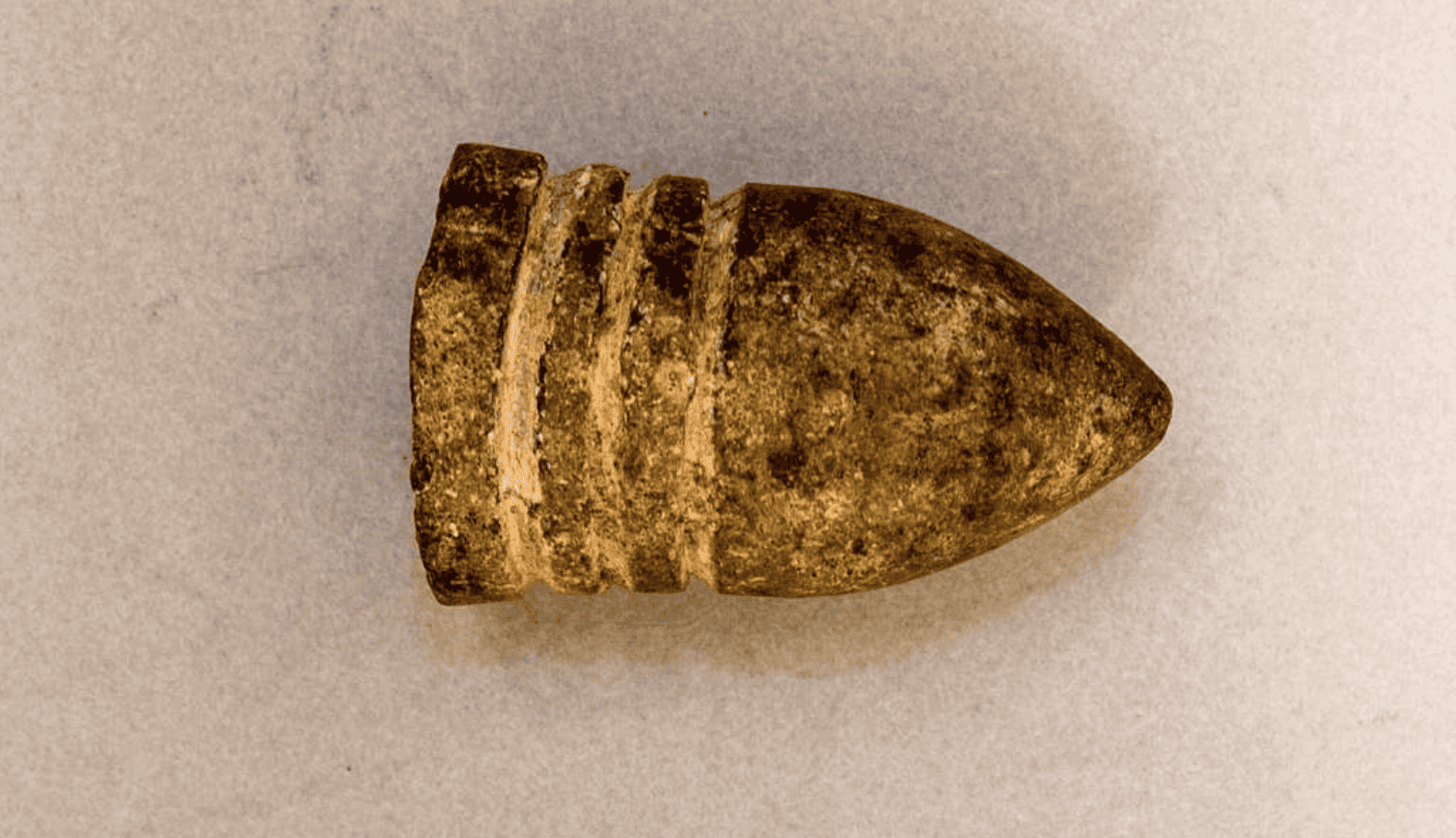

A Civil War bullet impregnated a woman

We included this one because it’s just too silly not to, and it makes it an excellent feel-good way to end an otherwise rather heavy and serious article. There is a surprisingly widespread myth that a bullet impregnated a young woman during the Civil War. The rumor states that a young man on a battlefield was shot, and the bullet passed through his scrotum, eventually hitting a young woman on a nearby porch in the abdomen. She survived the bullet wound and fell pregnant from the bullet embedded in her uterus. This story is not even remotely true.

Truth: It never happened

Snopes goes deep into the source of this mythological bullet pregnancy. Their fact-checkers found that the story was first published in The American Medical Weekly on Nov. 7, 1864, by Dr. Legrand Capers as a joke. However, like many jokes published in the media, it got a bit out of hand and now pervades modern society with its legacy.