Priceless works of art, objects, and collections have existed for centuries. One of the oldest treasures in the world, the Varna Necropolis, dates back to the 5th century BCE. People in myriad cultures throughout history have created fantastic works of art or adornments, mined precious minerals and gems, and amassed great treasures, which were often acquired by looting other treasures. Since the existence of these renowned treasures – priceless works and objects and collections – they have been stolen or gone missing without explanation.

Tumultuous events such as revolutions, wars, or natural disasters have often contributed to the theft or disappearance of these precious works when it is difficult to protect them. While these treasures are sometimes recovered, many of these renowned treasures remain missing and others are in danger of being destroyed. (Here are 25 cultural treasures destroyed forever by war.)

Since the earliest civilizations, armies have been plundering treasure. In the first century A.D., the Roman army took the menorah, a seven-branched candelabrum, from the Second Temple in Jerusalem, transporting it to Rome, where it eventually vanished. Treasures such as Japan’s Honjō Masamune sword, the Royal Casket of Poland, and Raphael’s “Portrait of a Young Man” were lost in the chaos of World War II.

Whether stolen, like the Crown Jewels of Ireland, simply vanished, like the Romanov Fabergé eggs, or lost at sea, precious artifacts have gone missing, to never reappear. Ships such as the São Vicente, the Flor de la Mar, and the Beatrice went to the bottom with untold treasure and irreplaceable artifacts – for instance, Incan relics or an ornate sarcophagus from Egypt. (These vessels are lost to time, unlike these, the most famous shipwrecks ever found.)

By reviewing information on sites including the Monuments Men and Women Foundation, 24/7 Tempo has compiled a list of renowned treasures that remain missing.

Here are lost treasures that have never been found

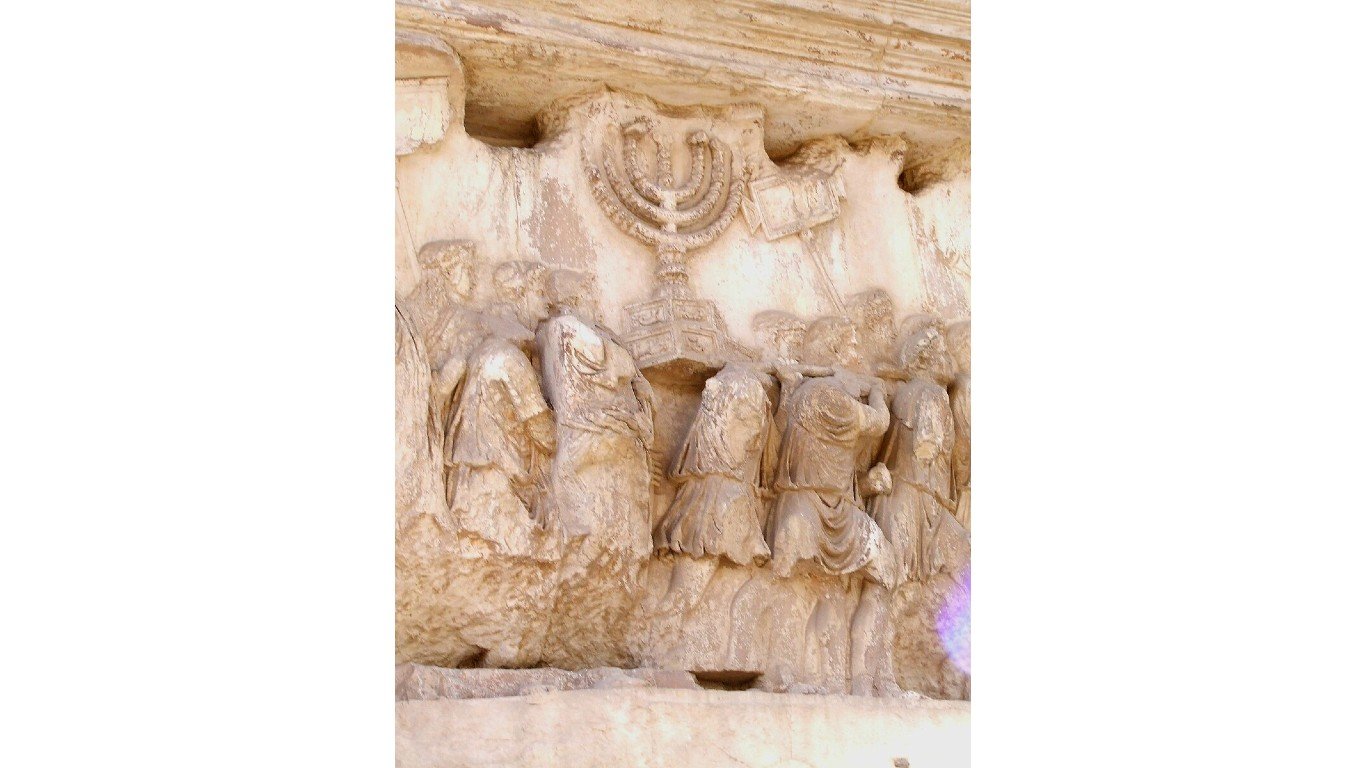

Menorah from the Second Temple

- Last seen: Second Temple, Jerusalem, 1st century

The menorah, a seven-branched golden candelabrum, was taken from the Second Temple in Jerusalem to Rome after a revolt in the province of Judea was quelled in the year 70. It was paraded through the city center in a triumphal procession to celebrate the victory of Emperor Vespasian and his son Titus. After the parade, most of the Temple’s treasures, possibly including the menorah, were deposited in the newly built Roman Temple of Peace. The menorah is mentioned in records when a rabbi reportedly saw it in Rome in the second century. However, after the Temple of Peace burned down around 192, the whereabouts of the menorah is unknown – though one account has it taken to Carthage by the Vandals in 455. A representation of the menorah is today the emblem of Israel

Treasure of Thibaud de Castillon

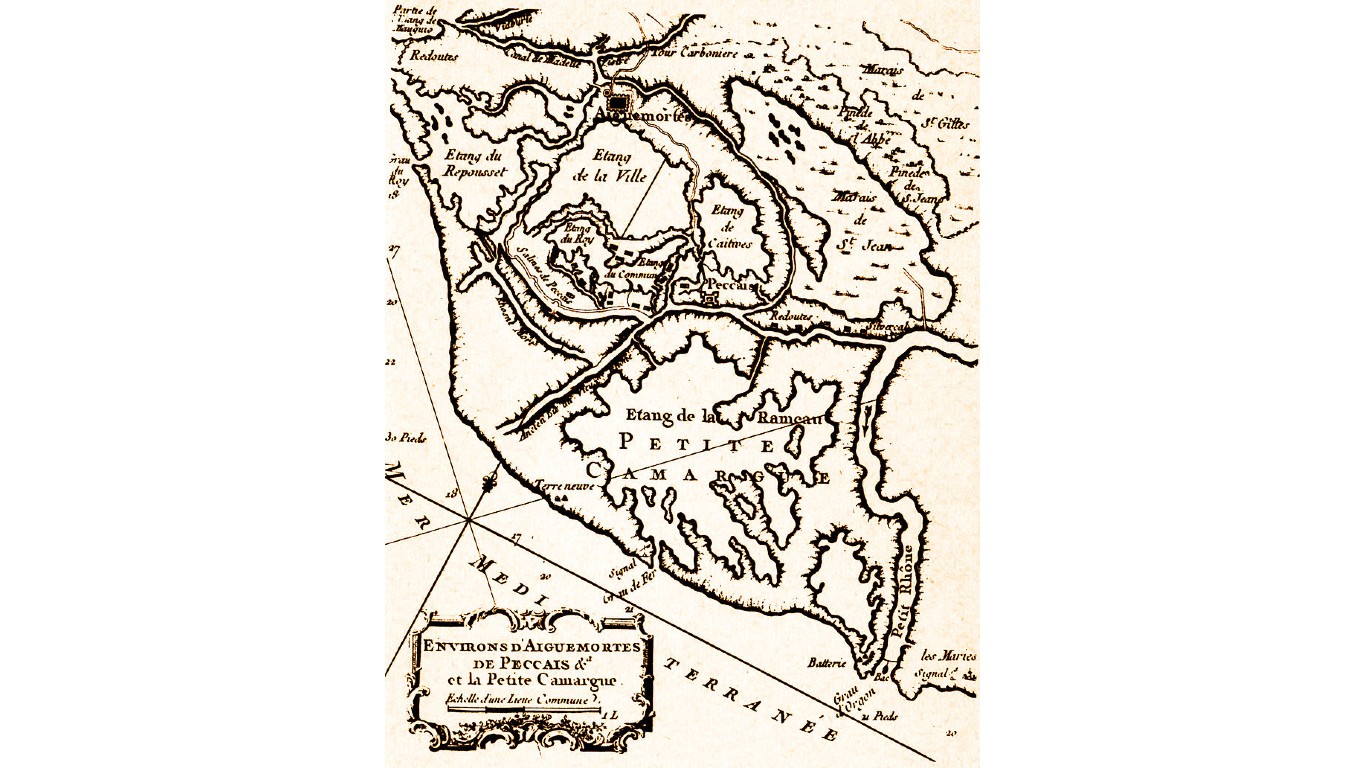

- Last seen: On the ship São Vicente near Cartagena, Spain, 1357

De Castillon, the bishop of Bazas in France, was given a position in Lisbon, where he reportedly used various wiles and influences to amass a huge fortune, including gold, silver, jewels, tapestries, and more. After his death, a Portuguese ship called the São Vicente was transporting his treasure from Portugal to France when it was ambushed by two pirate ships near Cartagena, on the Spanish coast. The ships, led by captains Antonio “Botafoc” and Martin Yanes, used overwhelming firepower that forced the vessel to surrender the treasure.

Later, Botafoc and his crew were captured near Aigues-Mortes, France, and the portion of the treasure they were carrying was used as gifts and payments for royalty, soldiers, courtiers, and staff. However, the second pirate ship, commanded by Yanes and probably carrying a good number of rare items, disappeared for good along with whatever treasure it was carrying.

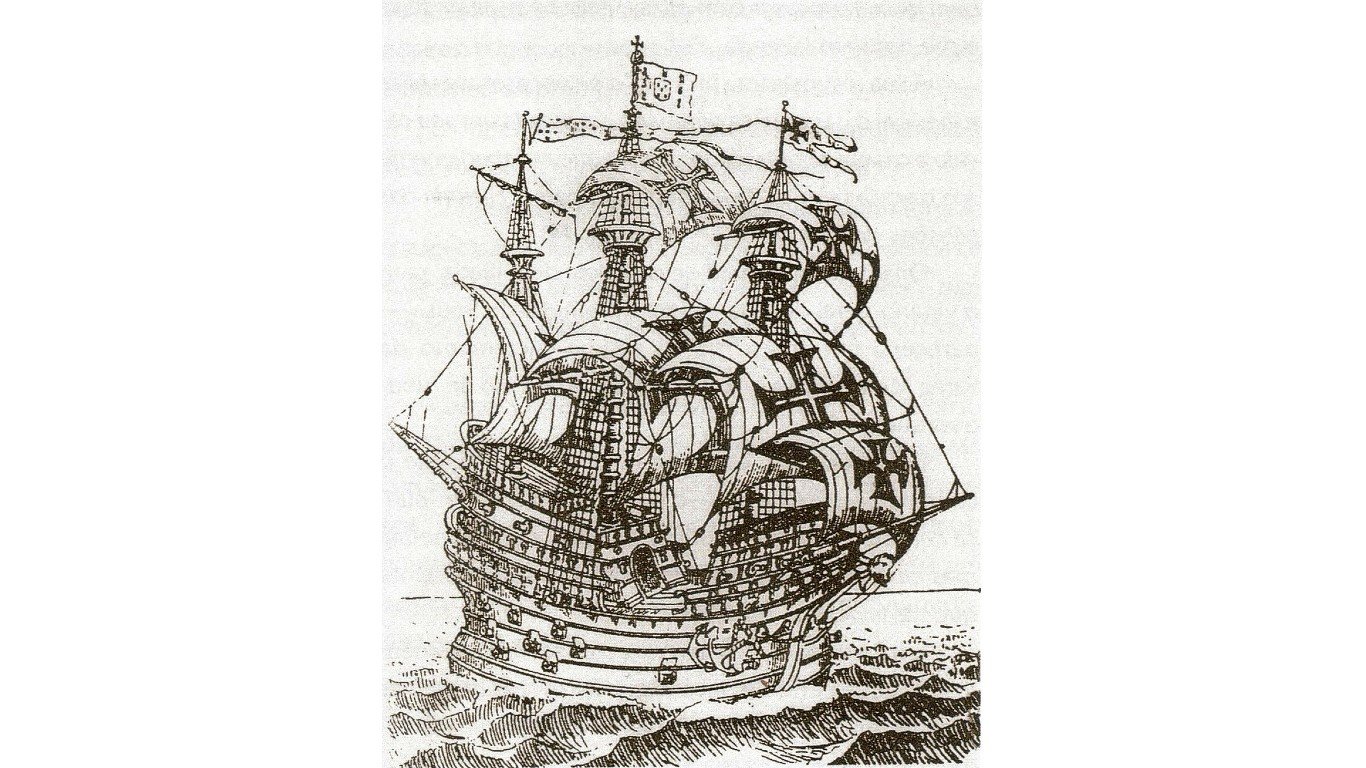

Treasure of the Flor de la Mar

- Last seen: Off the coast of Sumatra, 1511

The Flor de la Mar, an immense Portuguese sailing ship, had undergone several major repairs and was barely seaworthy at the time of its final journey. Caught in a storm near the northeastern coast of Sumatra, it tried to seek refuge on the coast but crashed into shoals, split in two, and sank. It was carrying a treasure – riches stolen by the Portuguese from the Sultan of Malacca – which was never found. While it is impossible to verify the exact contents of the treasure, modern speculation suggests that it amounted to more than $3 billion worth (in today’s dollars) of gold, diamonds, rubies, emeralds, coins, jewels, and rare hand-drawn maps by Javanese artists.

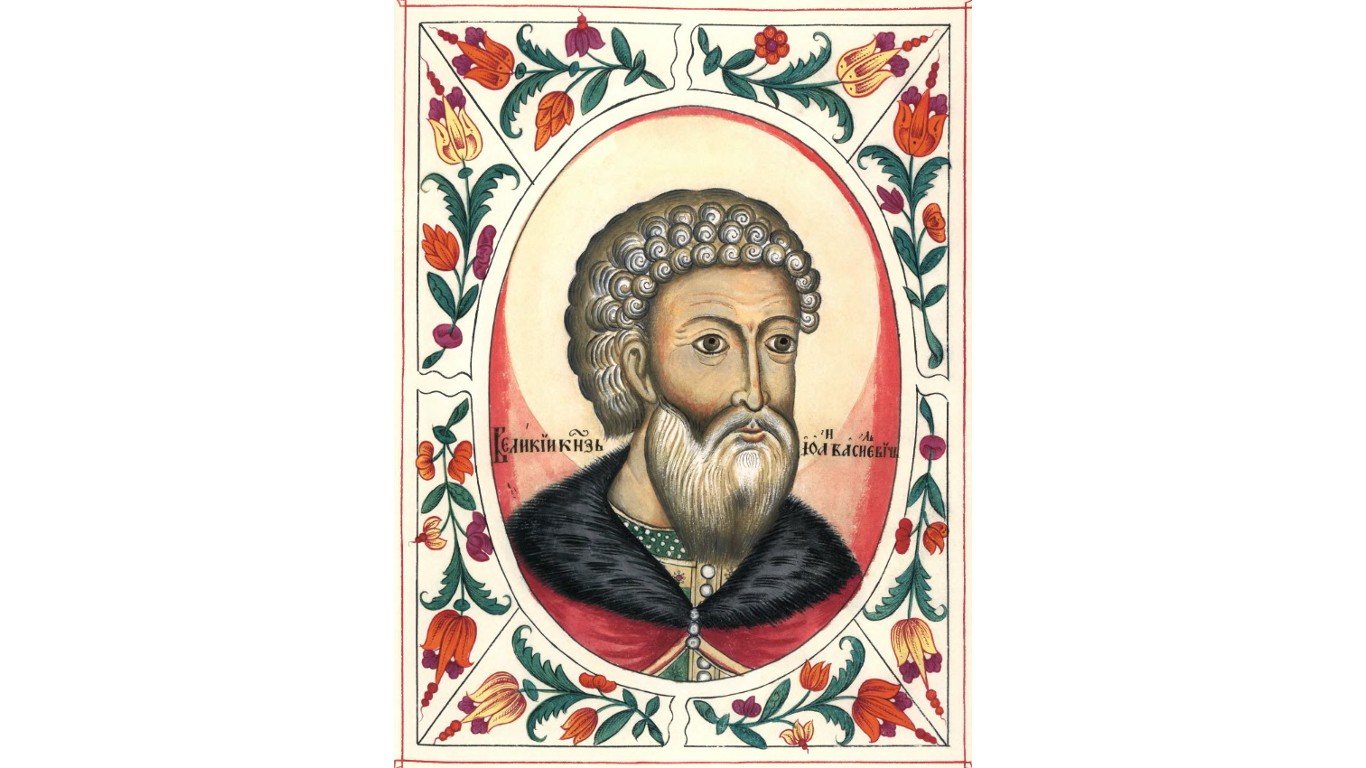

Library of the Moscow Tsars

- Last seen: Moscow, Russia, 16th century

It has been claimed that the rulers of Moscow, before the Romanov dynasty, built up a large library of ancient Greek and possibly Roman and Egyptian texts, called the Golden Library or the Library of the Moscow Tsars. The earliest reference to it comes from a scholar who visited the collection in 1518. Legend says that Ivan the Terrible, who ruled from 1533 to 1584, hid away the library’s manuscripts. For centuries, people have tried unsuccessfully to find this legendary lost library. While its existence remains questionable – some scholars consider it a myth – there are many old texts in Greek and other languages located in archives in Moscow and St. Petersburg today, which may or may not have come from the mysterious library.

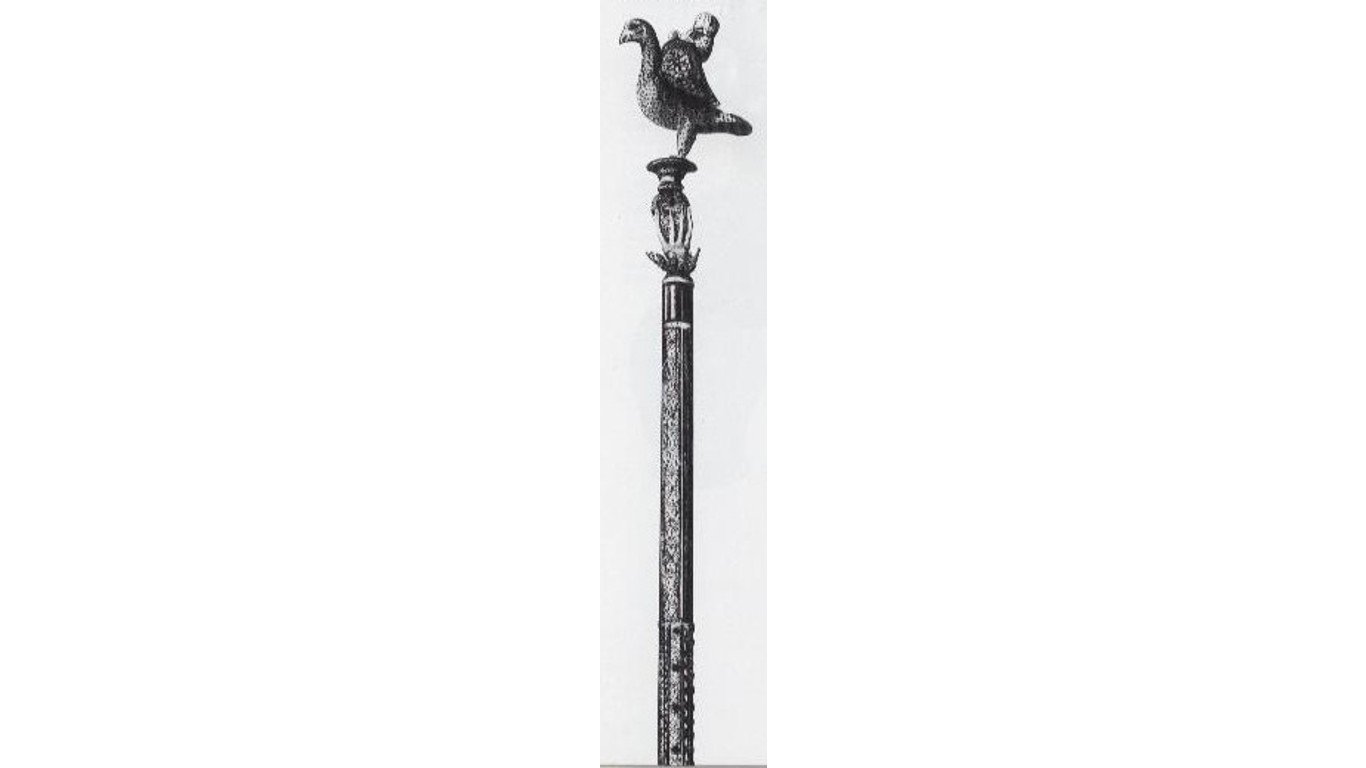

Scepter of Dagobert

- Last seen: Basilica of Saint-Denis, France, 1795

The Scepter of Dagobert was part of the ancient French Crown Jewels and possibly the oldest piece in that collection, dating back to the 7th century. It was named after the French King Dagobert I and said to have been made by goldsmith Éloi de Noyon, subsequently canonized as Saint Eligius. The scepter was kept in the Basilica of Saint-Denis until 1795. During the chaos of the French Revolution, it was stolen from the basilica. Despite being such an important historic relic, the Scepter has never resurfaced.

The Esperanza’s treasure

- Last seen: Spanish ship Esperanza off Peru’s Pacific Coast, 1816

The Esperanza was a Spanish ship that set sail from Callao in Peru in 1816, headed for the West Indies around Cape Horn. It is said to have been carrying a treasure, including 1.5 million gold escudos, an equal amount of silver, and possibly some Incan artifacts, all looted from the Viceroyalty of Peru. As it sailed down the coast, according to the account of a survivor, it was damaged by a storm, and then looted by pirates, who made off with the treasure. They were in turn ravaged by a storm themselves and struck a reef on Palmyra Atoll, about a third of the way between Hawaii and American Samoa. Legend has it that the pirates distributed some of the treasure amongst themselves, and buried the rest on the island, but it has never been found.

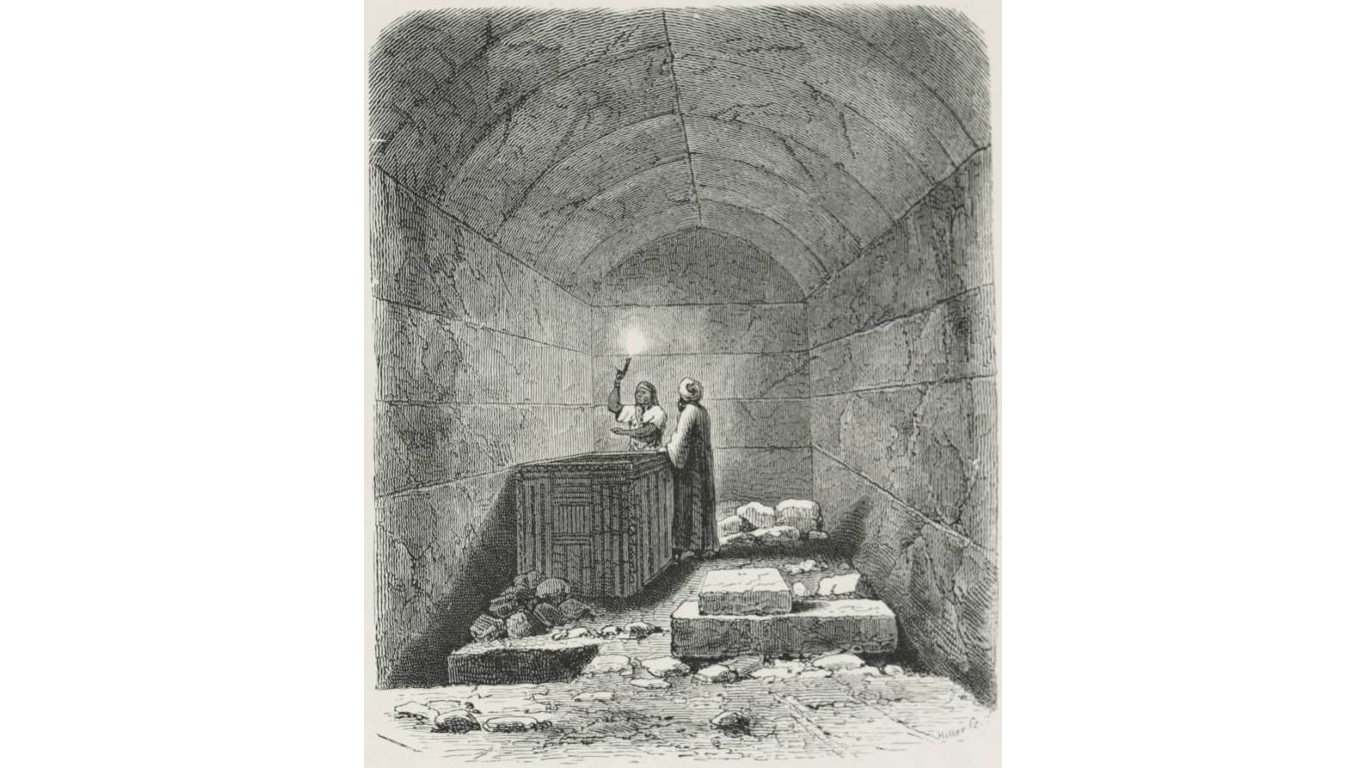

Ornate sarcophagus of Pharaoh Menkaure

- Last seen: Merchant ship Beatrice, off the coast of Malta, 1838

In 1837, British soldier and Egyptologist Howard Vyse discovered what may or may not have been the sarcophagus of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Menkaure inside the smallest of the three Giza pyramids. The following year, he shipped the sarcophagus to England aboard the merchant ship Beatrice – but it sank after leaving port in Malta with the sarcophagus aboard. In 2008, Spanish and Egyptian archaeologists collaborated to try and locate the sunken vessel. Dr. Zahi Hawass, then head of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, believed the wreck would be found not near Malta but off the Spanish city of Cartagena, but it did not turn up and the search continues for Menkaure’s ornate sarcophagus.

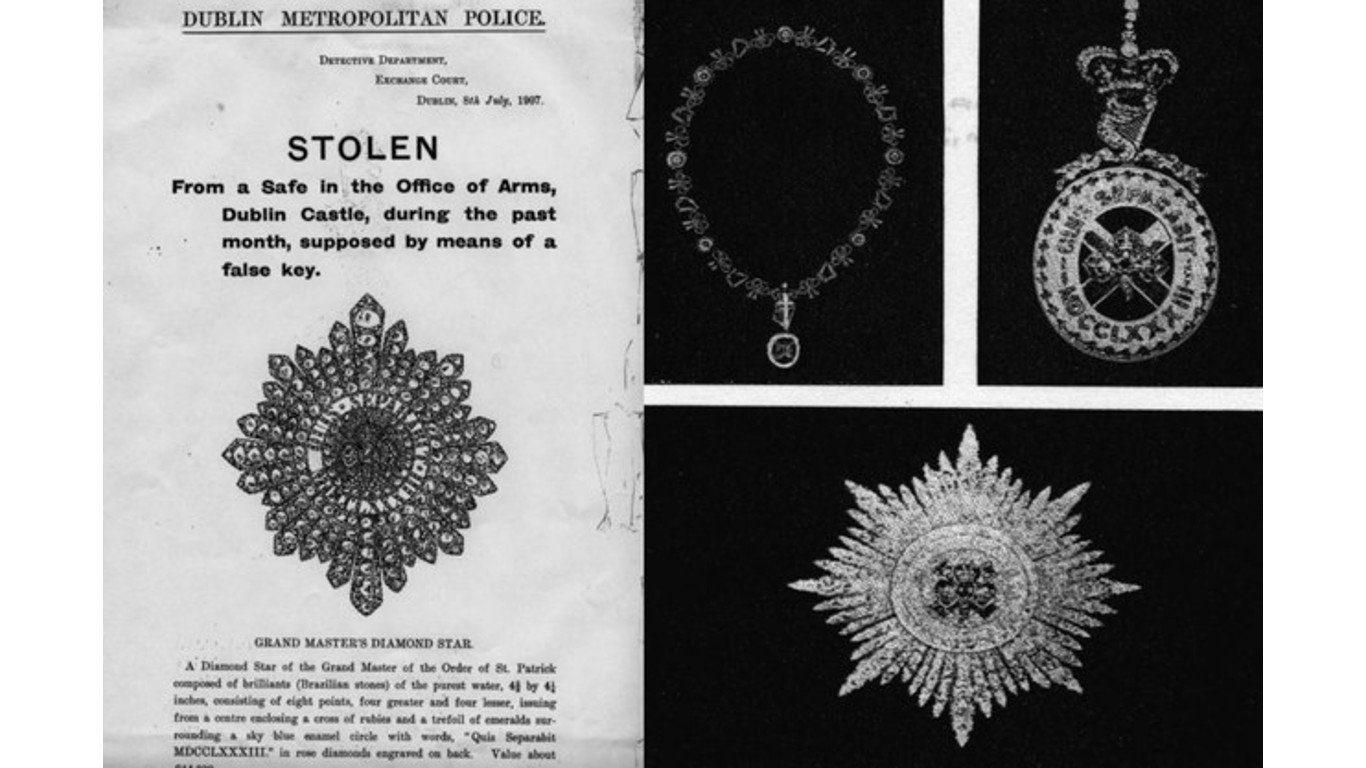

Crown Jewels of Ireland

- Last seen: Dublin Castle, 1907

The Irish Crown Jewels were not linked to royalty, but rather to the elite Order of St. Patrick, an Anglo-Irish order of knighthood established by King George III. The jewels included a star with Brazilian diamonds, a diamond badge, and five decorative gold collars. In 1907, they vanished. They were last documented in a safe in Dublin Castle on June 11 but found missing on July 6, with various security breaches in between. Despite intense investigation, the jewels were never recovered and remain lost over a century later. The prime suspect was convicted fraudster Francis Shackleton, brother of explorer Ernest Shackleton, though theories abound involving both Republican groups and Unionist groups, or even the British monarchy itself.

Romanov Fabergé eggs

- Last seen: St. Petersburg, Russia, 1917

The famous Fabergé eggs were colorful gem-encrusted and illustrated Easter eggs made out of silver, gold, or other precious metals by Russian jeweler Peter Carl Fabergé for the Romanov royal family between 1885 and 1916. A total of 69 eggs are known to have been created. After the Romanovs were executed in 1917 during the Bolshevik Revolution, six of the eggs – belonging to Maria Feodorovna, the onetime Empress of Russia – went missing in the chaos and are still unaccounted for. The known eggs are worth millions of dollars apiece. One, made of 18k gold and encrusted with sapphires and diamonds, with a gold-and-diamond lady’s watch inside, sold for an estimated $33 million in 2014.

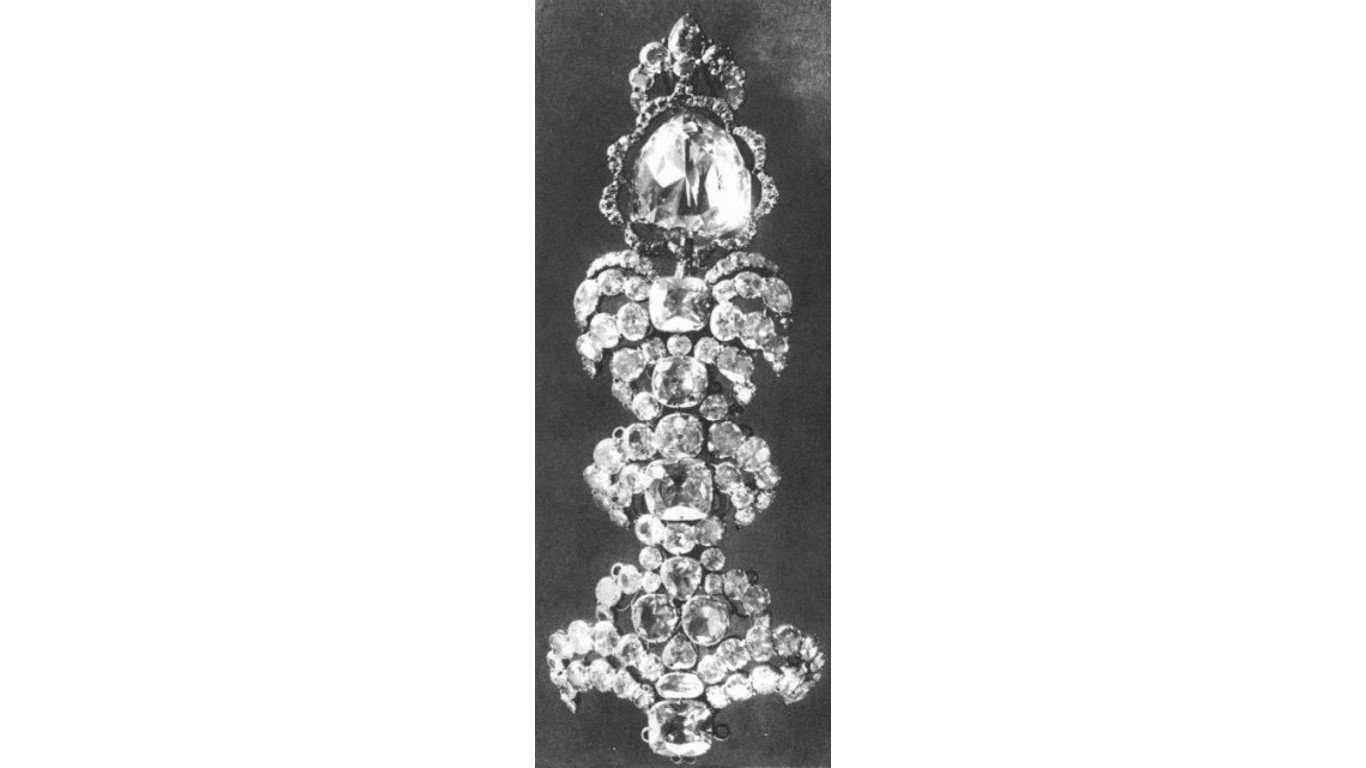

The Florentine Diamond

- Last seen: Bank vault in Switzerland, 1918

The Florentine diamond has a long, mysterious history. The 137.27-carat stone likely originated in India and came to Europe in the 15th century. One theory is that Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, acquired it and had it on his person when he died in battle. The gem later went to the Habsburgs of Austria-Hungary around 1743. The last Habsburg emperor, Charles I, fled with it to Switzerland after being deposed. He gave the diamond to Austrian lawyer Bruno Steiner to sell, along with other royal jewels. What happened next is unclear. A 1924 report said that Steiner was charged with fraud in connection with its disappearance, but he was acquitted. One rumor is that the diamond was sold in the U.S. in the 1920s and cut into smaller stones.

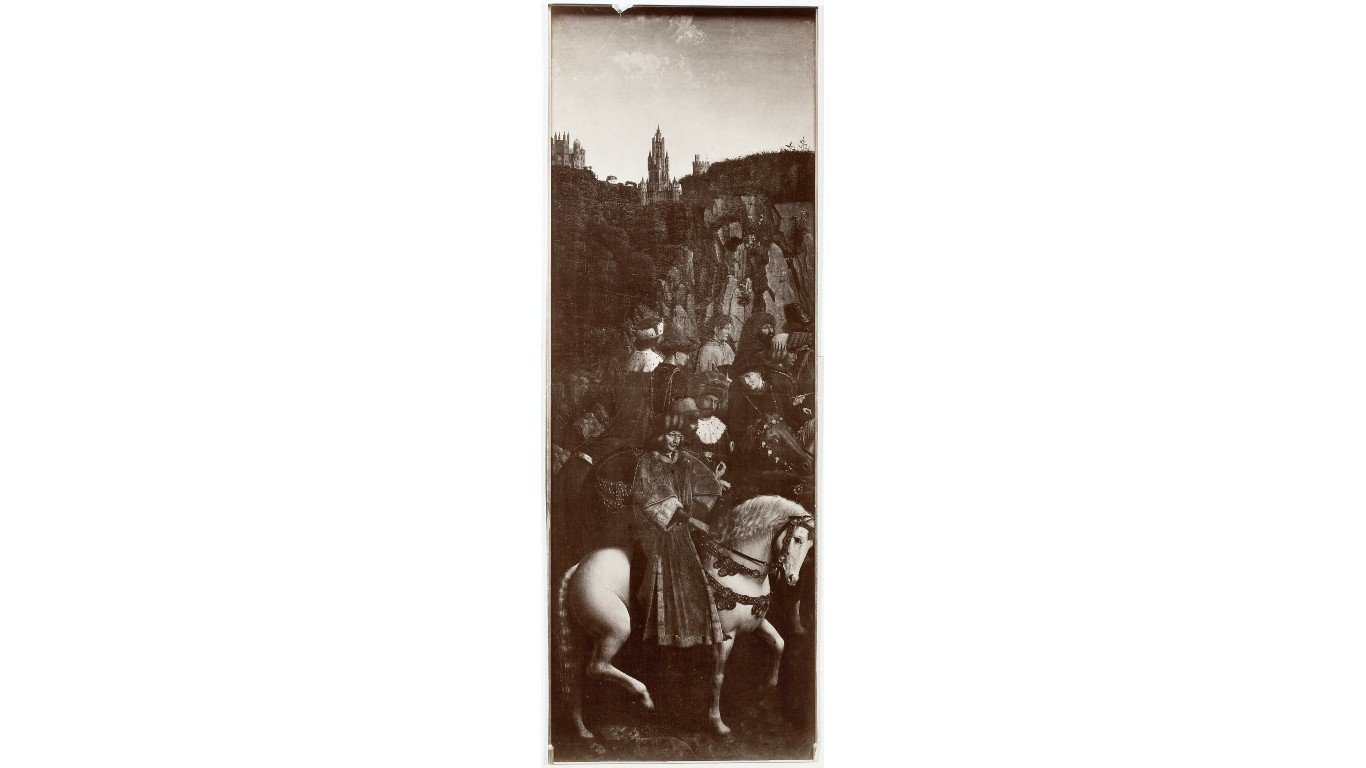

‘Just Judges’ panel of the Ghent Altarpiece

- Last seen: St. Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent, Belgium, 1934

The “Just Judges” or “Righteous Judges” panel was part of the 15th-century Ghent Altarpiece painted by Jan Van Eyck or his brother, Hubert, for Saint Bavo’s Cathedral in Belgium. It shows mysterious figures on horseback, possibly representing the Duke of Burgundy. In 1934, this priceless 33-foot panel was stolen from the cathedral and never found. A thief named Arsène Goedertier claimed as he was dying that he had taken the masterwork and that its location would go with him to his grave. It was never found, but tips about its location still come in. Art historian Noah Charney says that the unsolved case file is 2,000 pages long and remains open today.

Honjō Masamune sword

- Last seen: Mejiro police station, Tokyo, 1946

The legendary Honjō Masamune sword was won in battle by General Honjō Shigenaga in 1561. It passed through many owners before coming into the possession of the Tokugawa family, where it remained for over 260 years. Its last known owner was politician Tokugawa Iemasa at the end of WWII. When the U.S. occupied Japan, families had to surrender their weapons. In December 1945, the Tokugawa family gave 14 swords, including the Honjō Masamune, to the Mejiro police station in Tokyo. In 1946, it was said to have been handed over to a U.S. soldier named Sgt. Coldy Bimore, but no record of such a person has been found.

Amber Room

- Last seen: Catherine Palace, St. Petersburg, Russia, 1941

The Amber Room was a chamber in the Catherine Palace in Saint Petersburg, decorated in amber panels, gold leaf, and mirrors. Believing it was of German origin, Hitler wanted to reclaim it as a symbol of German pride. The Amber Room walls were discovered hidden behind wallpaper at Catherine Palace and taken by the Nazis to Königsberg Castle in what was then Germany and is now Kaliningrad, Russia.

As Germany was losing the war, Hitler ordered looted items moved from Königsberg to safer locations, but the city was heavily bombed by the Allies, and the castle was damaged by Soviet artillery. It’s widely believed the Amber Room was destroyed, but some believe it survived. Its ultimate fate remains a mystery, but in 1979, Russian artisans, with financial support from Germany, began reconstructing it at the Catherine Palace, taking 24 years to complete the job.

Peking Man fossils

- Last seen: Vanished while transported to New York City, 1941

In 1923, fossils of Peking Man, an ancient hominid possibly dating back as much as 750,000 years, were discovered in a cave near the village of Zhoukoudian outside Beijing. These significant fossils went missing in 1941 during the Japanese invasion of China when they were taken by U.S. Marines from Peking Union Medical College to be loaded onto a ship sailing to New York. Their whereabouts after leaving the school are unknown, but some theories suggest the fossils were lost at sea while being transported to the U.S., while others think they may be buried under a parking lot back in China.

Royal Casket of Poland

- Last seen: Kraków, Poland, 1939

The Royal Casket was a treasure box containing gold and silver relics of various monarchs of Poland and elsewhere. Moved to the Czartoryski Museum in Kraków, Poland, for protection during the November Uprising of 1830, it was hidden behind a brick wall on the palace grounds. During the Nazi occupation in WWII, the casket’s location was revealed by a German employee of the Czartoryski family, and the Nazis found and looted its precious contents. Some museum items were recovered after the war, but the Royal Casket itself and most of the valuable royal treasures inside have never resurfaced.

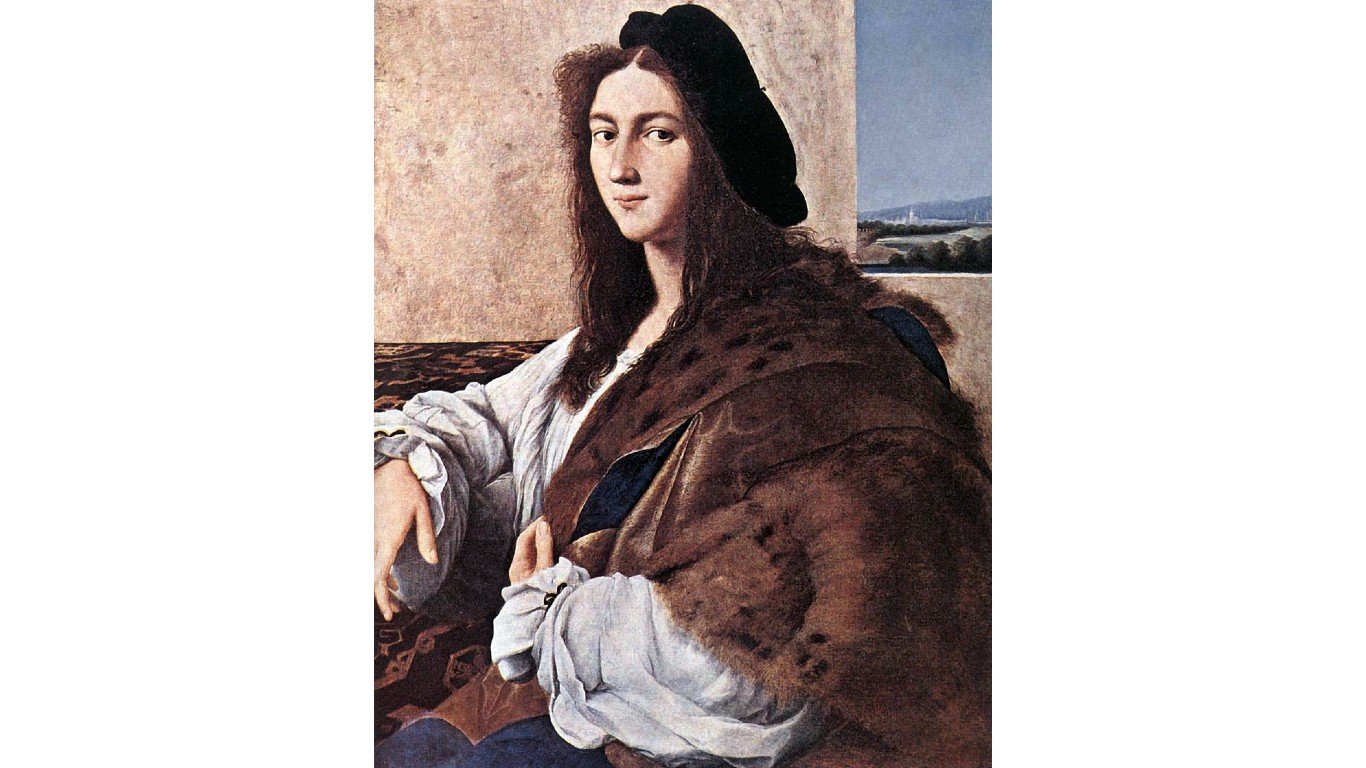

Raphael’s ‘Portrait of a Young Man’

- Last seen: A Nazi official’s chalet in Neuhaus on Lake Schliersee, Germany, 1945

The Italian Renaissance artist Raphael painted a work called “Portrait of a Young Man” around 1513. Its subject is unknown, though some think it might be a self-portrait. Like the Royal Casket of Poland, it was housed in the Czartoryski Museum in Kraków, but it too was found by the Nazis during their 1939 invasion. They planned to install it in the projected Führermuseum in Hitler’s hometown of Linz, Austria, but the museum was never built. The painting was last seen in 1945 in the chalet of a German official who was later executed for war crimes. Raphael’s looted masterpiece remains missing over 75 years later, though the Czartoryski Museum has offered a $100 million reward for its return.

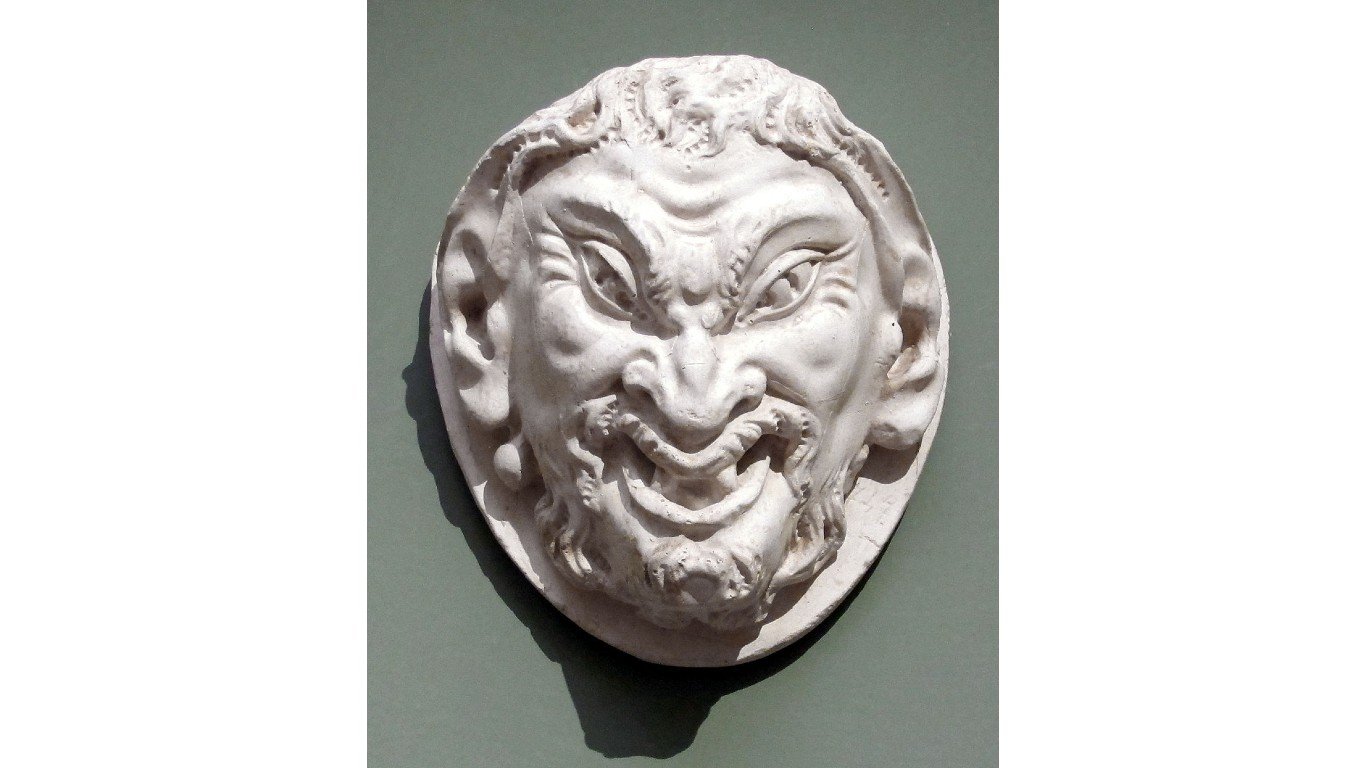

Michelangelo’s ‘Mask of a Faun’

- Last seen: Near Forli, Italy, 1944

The “Mask of a Faun” (also called the “Head of a Faun”), a marble sculpture of the mythological creature who was half-man and half-goat, has long been thought to be the work of Michelangelo, who may have sculpted it when he was only 15. It belonged to the Bargello Museum in Florence until it was looted by the Nazis in 1944. German soldiers stole the mask and transported it away on a truck last spotted near the Italian town of Forli. Despite searches after the war, the masterpiece has never resurfaced.

Caravaggio’s ‘Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence’

- Last seen: Chapel in Palermo, Sicily, 1969

Caravaggio’s masterful “Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence,” stolen in 1969 from the Oratory of Saint Lawrence in Palermo, Sicily, remains one of the world’s most sought-after missing artworks. The notorious theft is believed to have been orchestrated by the Mafia, with the painting eventually given to mob boss Gaetano Badalamenti. Though the parish priest was contacted to broker its return, the painting has never resurfaced. Experts fear rolling up the fragile, centuries-old canvas likely caused irreparable damage. After more than 50 years, investigators still chase leads on the lost treasure, most recently following an informant’s tip to search in Switzerland, because Badalamenti may have sold it to a Swiss dealer.

Tucker’s Cross

- Last seen: Bermuda Maritime Museum, 1975

The prized Tucker’s Cross, a glittering 22-karat gold cross studded with seven emeralds, was discovered in 1955 by treasure hunter Teddy Tucker amid the wreckage of a 16th-century Spanish galleon off Bermuda’s coast. Considered one of the most valuable pieces of sunken treasure ever recovered, the dazzling relic was temporarily housed at the Bermuda Maritime Museum for Queen Elizabeth II’s visit in 1975. Before the monarch arrived, Tucker realized that a plastic replica had been swapped for the priceless original. Though local police, the FBI, and Interpol investigated, the cross was never recovered and no arrests were made.

Jules Rimet World Cup trophy

- Last seen: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1983

The stolen trophy was a 12-inch statuette of the Greek goddess Nike, made in 1929 by French sculptor Abel Lafleur, and awarded every four years to the winner of soccer’s World Cup. Though called the Golden Trophy, it was not solid gold, but silver coated in gold. In 1966, the trophy was stolen from an exhibition hall in London but quickly recovered. In 1970, Brazil was given the trophy permanently after winning its third World Cup, but in 1983 it was stolen from the Brazilian Football Confederation headquarters. Four suspects were arrested, but all escaped. Two died before they could be apprehended and two served jail sentences, though not for the trophy theft. No one knows what happened to the trophy, but a replica was given to the BFC in 1984.

13 art masterpieces

- Last seen: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts, 1990

Thirteen masterpieces with a total value of $500 million were brazenly stolen from Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1990 by two thieves posing as police officers. They overpowered guards and spent 81 uninterrupted minutes cutting precious works by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Degas, and Manet from their frames. Per Gardner’s will, the empty frames still hang in the museum, to be filled only by the original stolen pieces. Investigators have chased leads suggesting that the art came under the control of local mobsters and was moved to Philadelphia for black market sale in 2002, but not a single item has been recovered. With a $10 million reward still offered, the Gardner theft remains one of the most notorious unsolved art heists.

Antwerp diamonds

- Last seen: Antwerp Diamond Center vault, 2003

In one of the most daring heists ever, a group of thieves bypassed multiple layers of top-tier security to steal $100 million in diamonds from an ultra-secure vault in Antwerp’s Diamond Center, the heavily fortified hub of the global diamond trade. Over a weekend, the robbers systematically dismantled security measures and breached over 100 safe deposit boxes brimming with diamonds and other valuables in the underground vault. Panic ensued when traders returned Monday to find vaults ransacked.

Despite their meticulous planning and execution in penetrating the world’s most secure diamond depository, the perpetrators – led by a prolific thief named Leonardo Notabartolo – were caught, and served prison sentences. Notabartolo later claimed that a diamond merchant had hired him and his gang to steal the valuables as an insurance scam. None of the loot was ever recovered, however.

Graff Diamonds jewelry

- Last seen: Graff Diamonds store on New Bond Street, London, 2009

On Aug. 6, 2009, two men dressed in sharp suits robbed the exclusive Graff Diamonds store in London in broad daylight. Over 25 minutes, they forced staff at gunpoint to open display cases and stole 43 high-value jewelry pieces worth about $65 million total. To escape, they fired shots to create confusion and drove off in a waiting BMW, switching getaway vehicles twice before vanishing. One robber left his cell phone behind, leading to the capture of the heist’s mastermind, Aman Kassaye, who was sentenced to 23 years. Three other men got 16 years each. Of the stolen jewels, only a 16-carat yellow diamond has been recovered. The rest are believed to have been swiftly sold off to waiting international customers.

Ivory Coast Crown Jewels

- Last seen: Museum of Civilisations, Abidjan, Ivory Coast, 2011

During a battle in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, priceless cultural treasures were stolen from the country’s main museum, including ancient royal gold jewelry, masks, statues, and religious artifacts dating back to the 17th century. Around 80 irreplaceable objects valued at $6 million were taken. The systematic nature of the heist, with no forced entry and display cases left intact, implied inside help. Some stolen pieces trace back to ancient Akan kingdoms, making them irreplaceable national relics. Expert thieves targeted and took the most valuable artifacts, though the whereabouts of these precious items remain a mystery.