Humans have long been fascinated with aviation. Legends involving flight date back to well before the common era. Some legends like that of the Greek Pegasus or that of Alexander the Great achieving flight with Griffins involve great, mythical beasts. Others, such as that of Icarus and Daedalus, involve feats of human engineering. The first kites were invented in China in 400 BCE and these flying toys became staples of early Chinese religious ceremonies.

The earliest recorded details for a potential flying machine by humans came from now-famous artist and inventor, Leonardo DaVinci in 1505–1506 when he wrote the Codex on the Flight of Birds, which contained sketches and notes on the nature of flight and early understandings of aerodynamic principles. One of the devices he planned in the book was the Ornithopter, which was never realized but is the basis of modern-day helicopters.

In more primitive times, people would try to fly by emulating birds. They would affix artificial wings with feathers to their bodies and try to flap their way into the sky. Other early engineering feats that would later serve as the basis of human flight include Hero of Alexandria’s steam-powered sphere. It mounted a sphere atop a water kettle with two L-shaped tubes on either side of the sphere. When activated, the steam from the water kettle would fill the sphere and be released through the tubes, allowing the gas to escape and causing the sphere to rotate.

To populate this list, we looked at a brief history of human aviation and identified the key breakthroughs that defined human flight as we know it. Then, we studied those key historical points in-depth. We aimed to source reputable, academic sources regarding aviation history, such as NASA. (Here’s a look at the most successful fighter pilots in history.)

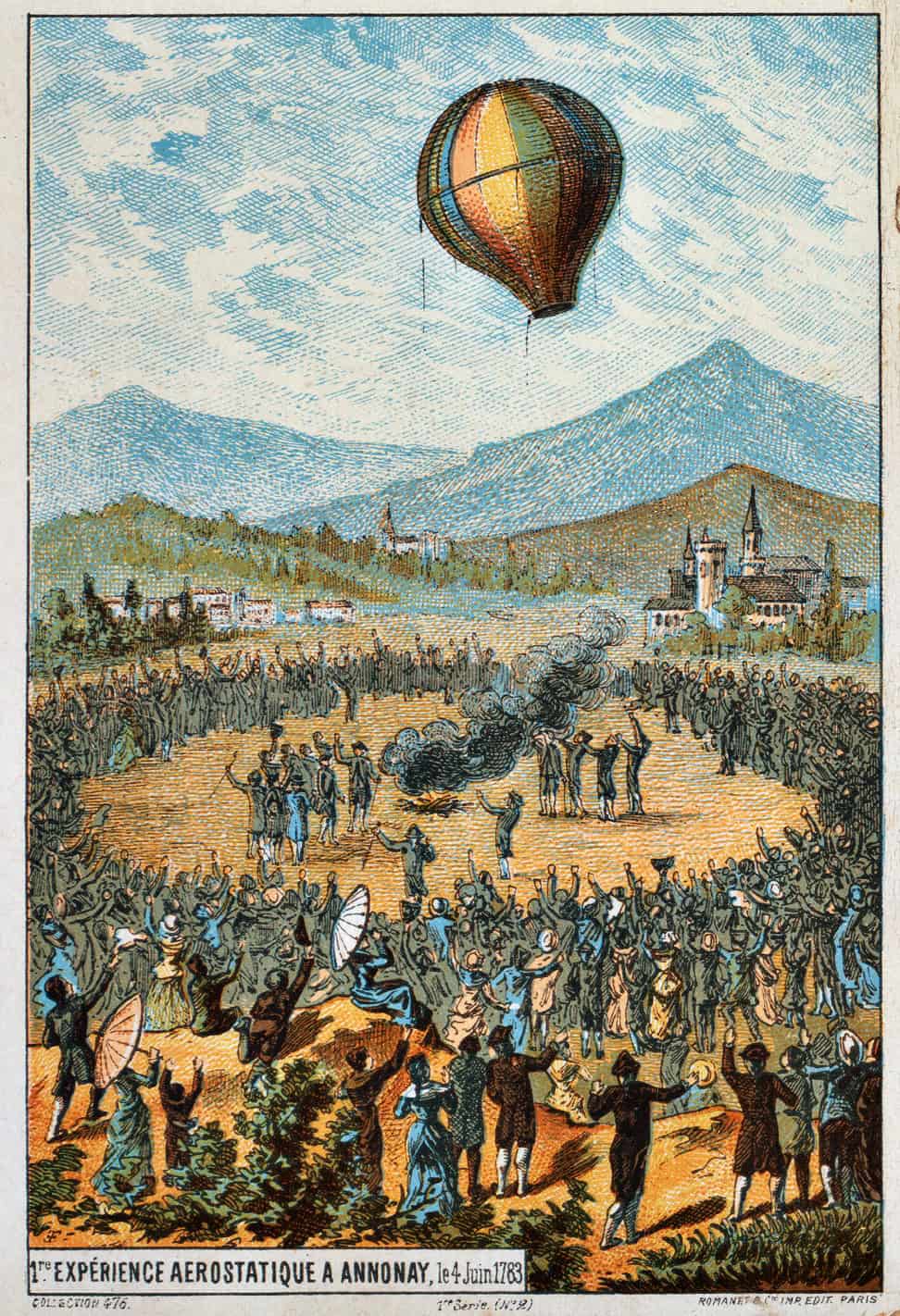

Nov. 21, 1783: The First Human Flies in a Hot-Air Balloon

In 1783, two paper-industry moguls, Joseph-Michale and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier discovered that when hot air was directed into a paper bag, the bag would rise into the air. This discovery would kickstart human aviation. They further applied this concept by developing a balloon made of silk and lined with paper, measuring 33 feet (10 meters) in diameter. From a marketplace in Annonay, they launched the first, unmanned balloon on June 8, 1783. The balloon rose to an altitude of around 5,200-6,600 feet and stayed in the air for 10 minutes, covering a bit over 1 mile of distance before it descended.

The success of the Montgolfiers’ invention spread quickly and they were soon granted an audience with the King of France. With the King’s funding, they began planning for manned balloon travel. However, they needed to be sure that human physiology would withstand the conditions of high altitudes, as humans had never been recorded in such states before then. Thus, they launched a balloon carrying a sheep, a duck, and a rooster. The duck, which flew of its own accord, acted as the control. The rooster, another bird but one that did not reach great altitudes, and the sheep, thought to be physiologically similar to humans, acted as the subjects to determine the relative safety of air travel for humans.

The experiment was a success and they began planning for human balloon travel after it. On Oct. 15, 1783, the Montgolfiers launched a human-manned balloon on a tether, which stayed up for about four minutes before descending. Then, finally, on Nov. 21, the Montgolfiers launched the first, untethered, human-manned hot-air balloon. One of those passengers would later become the first victim of balloon travel when he attempted to cross the English Channel by balloon, and the balloon exploded.

1876: The Advent of the Internal Combustion Engine Makes Heavier-Than-Air Travel Possible

Before the invention of the internal combustion engine, air travel was limited to “lighter than air” travel. This meant that aviation machines, such as the hot-air balloon, relied on using high concentrations of gases that were lighter than air, such as hydrogen, to lift the device into the air. However, the power output of the internal combustion engine made it possible to generate enough lift that a machine could potentially lift off the ground without requiring it to be “lighter than air.” The use of internal combustion engines to generate the required thrust for a device to move itself is the basis for all engines, such as gasoline, diesel, gas turbine, and rocket-propulsion systems.

ICEs gain energy from the heat released during the combustion of the oxidizer-fuel mixture. The hot, gaseous products of combustion act on the moving surfaces of the engine, such as a piston, turbine blade, or nozzle to move parts of the machine and generate power. These engines are the most widely used and broadly applied power generation devices.

Internal combustion engines largely replaced the steam-powered engine. Steam power was a crucial factor in developing human travel methods. Many early transportation devices, such as steam-powered railways, provided critical knowledge of the physics and mechanics of generating power. However, early steam engines typically weren’t powerful enough to move large objects vertically the way we know them today. Early steam-powered aircraft couldn’t reach the heights needed or stay in the air long enough to make long flights and their low horsepower limited how much weight they could carry. The last design for a steam-powered aircraft was in the 1960s. Several steam engine aircraft had been hypothesized during the 1900s, but few ever made it to the prototype stage.

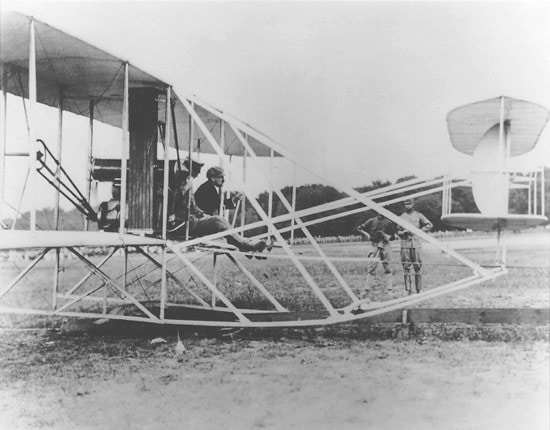

Dec. 17, 1903: The Wright Brothers Make Their First Successful Flights

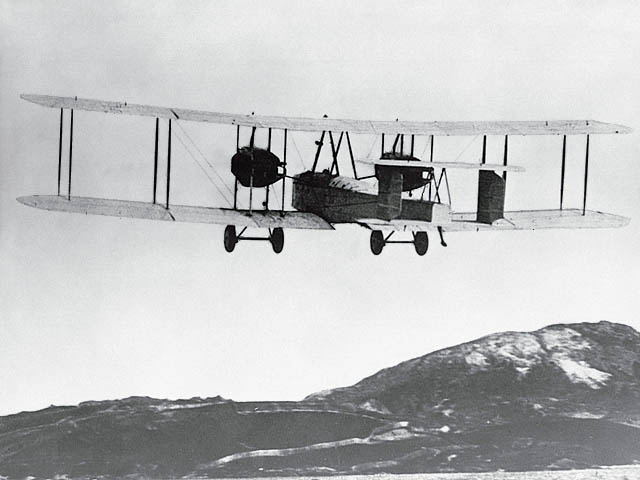

Before 1903, most manned aviation feats had been “lighter than air” aircraft. There were a few notable manned aircraft flights in the mid to late 1800s, but these flights were not level, sustained, or controlled. This changed when Wilbur and Orville Wright achieved a sustained, level flight in their personally designed, heavier-than-air aircraft. Wilbur and Orville were unique within their family. Unlike their brothers, these two did not attend university. However, a lack of a degree did not mean they were incapable or unintelligent. Quite the contrary; they were gifted engineers.

They began their journey by writing to the United States Weather Bureau to ask where a good place to conduct glider tests was. After settling in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, they took their aircraft there and began conducting experiments. They built a wind tunnel where they tested nearly 200 different wing and frame designs. Additionally, with the help of decorated machinist, Charles Taylor, they developed a 12-horsepower combustion engine, enough to power their flight, in theory.

The Wright brothers transported their final aircraft to Kitty Hawk in pieces and assembled it for takeoff. After a few extra tests, they were ready to fly. On Dec. 14, Orville attempted the first flight. However, the engine stalled and the aircraft was damaged, forcing them to spend a few days repairing it. Three days later, they achieved the first powered, sustained, controlled flight in history. Each brother flew their aircraft, dubbed the Wright Flyer, twice for a total of four flights. The shortest flight was just 12 seconds and the longest was 59 seconds. However, flight experts and the press were hesitant to even believe flights occurred, and those that did considered the flights too short to be significant.

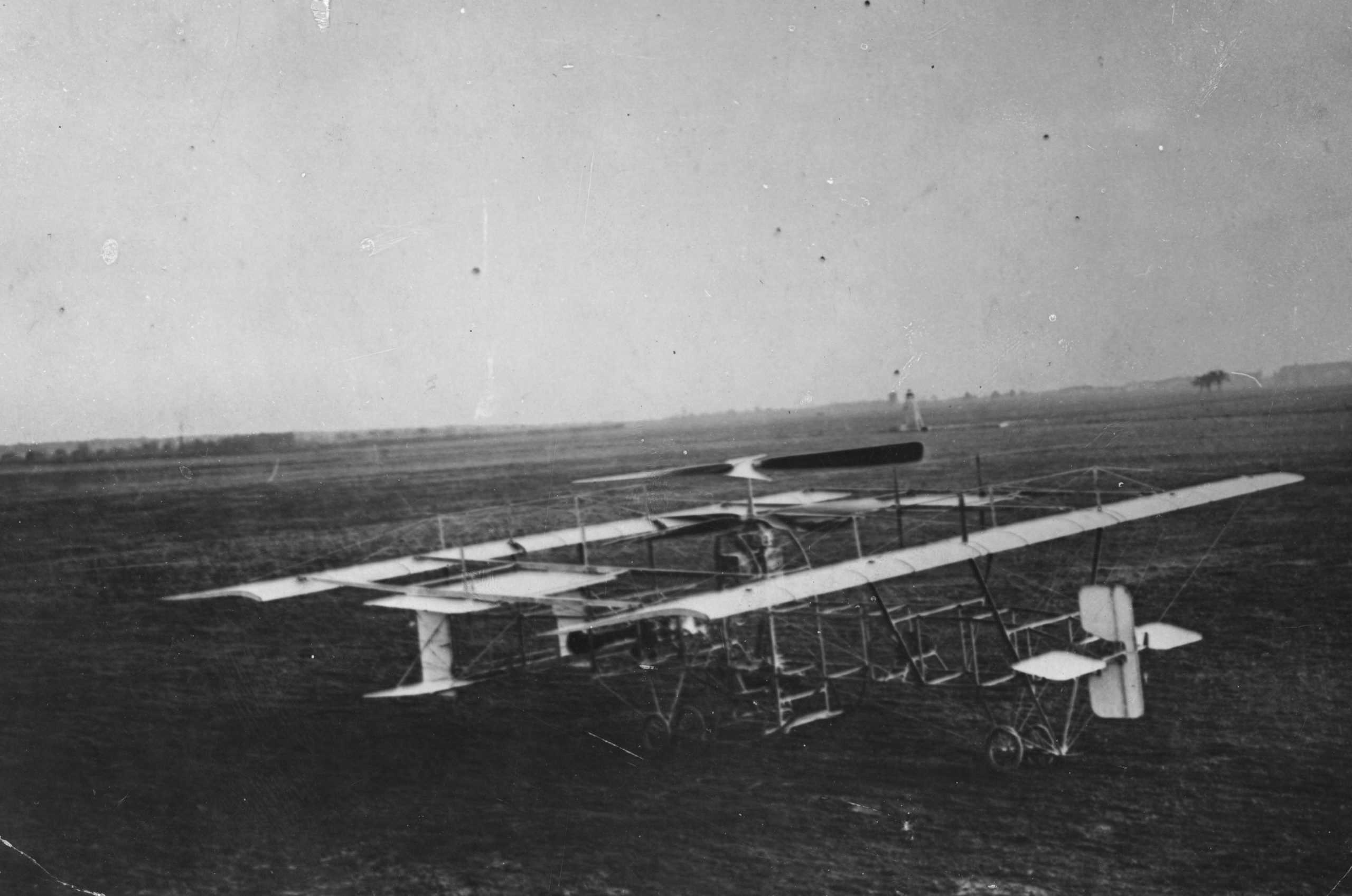

1907: The First Helicopter Takes Flight

While the Wright brothers were working on biplanes, Louis and Jacques Breguet in France were working on the first helicopter. We admit that their first prototype, the Gyroplane No. 1, looked nothing like a modern helicopter. However, it was the first machine to independently raise itself off the ground using a rotating wing system to generate lift. The Gyroplane No. 1 didn’t reach the impressive heights that modern aircraft enjoy. It rose to just 0.60 meters on its first test and 1.50 meters on its second test. However, its engineering was crucial for the development of modern helicopters.

Gyroplane No. 1 had 32 total small lifting surfaces. It used a rectangular chassis made of steel tubing that supported a powerplant and a pilot. Each corner of the chassis had a steel tubing arm that held a 4-blade biplane rotor covered in fabric. The diagonally opposed rotors rotated in the same direction, with one pair spinning clockwise and the other spinning counterclockwise. Due to the constraints of the device, everything had to be as light as possible. Thus, the pilot was, in part, hand-picked because he was physically smaller than average, weighing just 68 kilograms.

The exact date of the first flight of the Gyroplane No. 1 is a subject of hot debate. Authorities argue about whether the first flight took place on Aug. 24 or Sept. 19, with proponents of both dates resolutely believing in their correctness. While this device’s flight was significant in the design of modern helicopters, it had some notable limitations. Most notably, the aircraft was neither controllable nor steerable, which was one of the greatest issues in air travel at the time.

1909: The First Modern Aircraft is Commissioned in the Military

Limited use of lighter-than-air aircraft in the military was documented in the late 1800s. The French National Convention authorized the formation of a military tethered-balloon organization, which would later become the French Aérostiers, formed on April 2, 1794. However, this effort was rather short-lived. The Aérostiers disbanded just five years later in 1799. Balloons were also used during the American Civil War and by the British Army in Africa from 1884 until 1901. However, it wasn’t until the early 1900s that true military aviation began to become prominent.

When Orville and Wilbur Wright began developing their aircraft, they believed that these machines would be useful for military reconnaissance. They were right as they received a contract with the military to design an aircraft in 1908. The specification called for an aircraft capable of carrying two people at a speed of at least 40 miles per hour for a distance of at least 125 miles. They delivered the aircraft in June 1909 and it was commissioned to the military as “Airplane No. 1, Heavier-than-air Division, United States aerial fleet.”

The most prominent aircraft at this time was not the airplane, but the airship. Those developed by a German engineer, Ferdinand, Count von Zeppelin were the most ambitious airship ventures of the time. These zeppelins could carry five 110-pound, high-explosive bombs and an additional 20 5.5-pound incendiary bombs at a time when most military aircraft were strictly for reconnaissance and had no armament at all. Experiments to arm airplanes began in a limited capacity in 1910 with attempts to mount machine guns on airplanes and the development of bombing techniques, resulting in the development of the first practical bombsights.

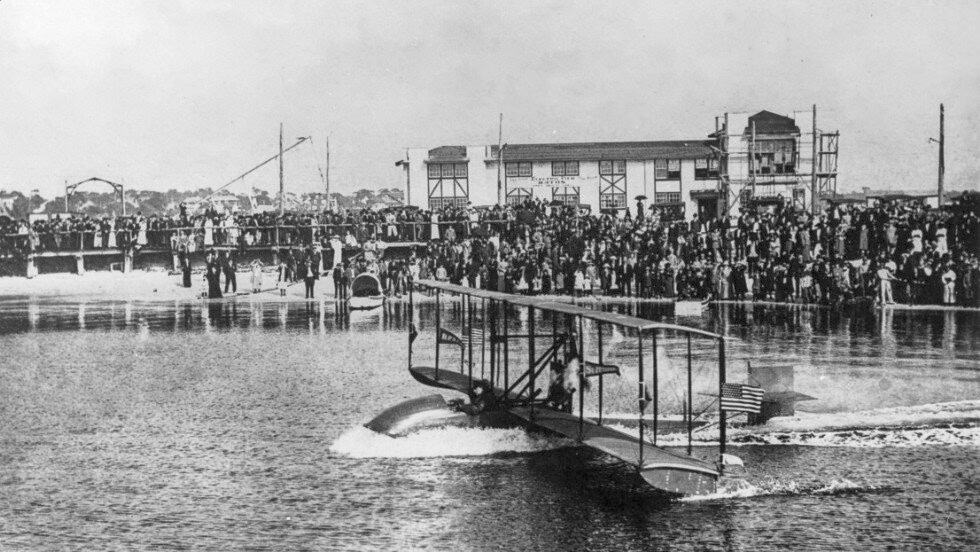

Jan. 1, 1914: The First Passenger Airline Flight Lifts Off

The first scheduled passenger air travel occurred in 1914. The flight used an airboat rather than an airplane, an aircraft designed to take off and land in the water rather than on land. It went from St. Petersburg, Florida, to Tampa Bay, Florida. Traveling from St. Petersburg to Tampa wasn’t an unusual feat at the time. However, the trip took a while with the resources available at the time. Getting to Tampa or St. Petersburg could take as long as 20 hours if one chose to drive around the bay in an automobile and the shortest travel option was still a two-hour steamboat ride across the bay. However, with aircraft technology at the time, the trip would theoretically take just 20 minutes in ideal conditions.

At the time, Thomas Benoist was designing “flying boats,” designed for air and land travel. A representative for a diesel engine manufacturer, Percival Elliott Fansler, became fascinated with these designs. He proposed that Benoist create an airline of flying boats between Tampa and St. Petersburg to reduce the travel time between the cities. Together, they handpicked a pilot for this endeavor and they chose the famed Tony Jannus. At the time, Jannus was a highly popular figure in aviation known for his adventurous flying and daredevil stunts. Aviation experts dubbed him the “epitome of the romantic flyer” and he agreed to pilot Benoist’s airboat.

Benoist and Fansler minted the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line in 1914 and the first flight took off on New Year’s Day. This flight had one passenger, Abram C. Pheil, former mayor of St. Petersburg. The flight lasted 23 minutes and didn’t experience any major interruptions or difficulties. Despite the success, the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line was a short-lived endeavor, operating for just four months before shutting down.

June 1919: First Nonstop Transatlantic Flight

While nonstop transatlantic flights happen every day in the modern era and typically take between six and 10 hours, the first time pilots achieved this feat was not so simple. The flight took off from Newfoundland, lasted 16 hours, and resulted in the aircraft crash-landing in a bog in Ireland. The aircraft in question was piloted by Capt. John Alcock and navigated by Aruthr Witten Brown. After landing, Alcock telegraphed his success to others stating, “We have had a terrible journey. The wonder is that we are here at all. We scarcely saw the sun or the moon or the stars. For hours we saw none of them.” The lack of celestial bodies was a significant feature of the flight since their only navigation tool was a sextant, which measure the position of celestial bodies in relation to the horizon.

To make matters worse, the weather was abysmal, the airplane was rudimentary, and the sky was covered in fog and clouds from the terrible weather. This flight occurred nearly a decade after the first transatlantic flight by Charles Lindbergh and was, in part, a response to a call from a travel enthusiast, Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe. The British newspaper tycoon was fascinated with new modes of travel and would put out cash prizes for engineers and operators who could achieve great feats with novel travel methods.

Northcliffe offered 10,000 pounds in cash, worth over 600,000 USD today, to the first pilot to travel from North America to anywhere in Great Britain or Ireland without stopping, within 72 hours. When he first put out the challenge, aircraft engineering hadn’t reached a point where this was feasible. However, during World War I, aircraft technology advanced rapidly in response to the war effort, and by 1914, pilots were ready to take the challenge.

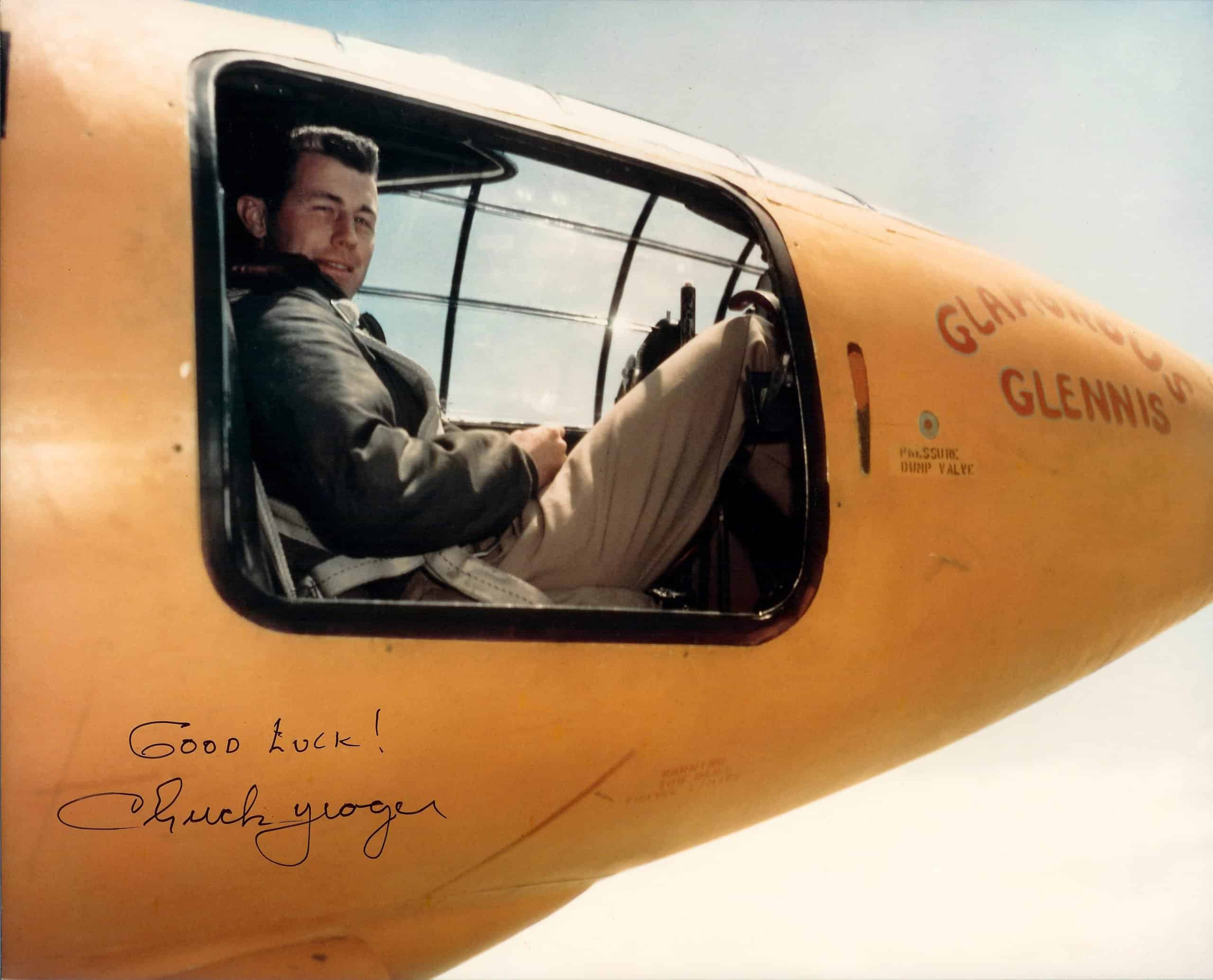

Oct. 14, 1947: Chuck Yeager Flies Faster Than Sound

At the beginning of the era of air travel, many people, even experts, believed that humans were not meant to fly faster than sound. Implements like bullwhips and stockwhips were capable of breaking the sound barrier. However, the idea of sending a human flying through the air so fast that they move faster than sound itself was a tall order. Many experts believed that doing so would cause the aircraft to fall apart and, naturally, kill the pilot. That didn’t stop people from trying, though. The Bell Aircraft Company was experimenting with faster-than-sound flight in the 1940s and they built the X-1 aircraft, a rocket plane designed to fly faster than sound.

Chuck Yeager was born in Myra, West Virginia, and was an Air Force combat pilot during World War II. He flew 64 missions over Europe and shot down 13 German aircraft. He was shot down once over France and escaped capture with the help of the French Underground. Yeager was one of several volunteers chosen to fly the X-1 in trials. On Oct. 14, 1947, Yeager was strapped into the X-1. The rocket plane was then lifted to 25,000 feet by a B-29 aircraft and released through the bomb bay.

The X-1, piloted by Yeager, shot up to 40,000 feet and reached a speed of 662 miles per hour, which is the sound barrier at that altitude. Yeager continued to serve as a test pilot for Bell Aircraft Company’s rocket planes and in 1953, he reached a speed of 1,650 miles per hour in the newer X-1A aircraft. He retired from the Air Force in 1975 at the rank of brigadier general and died in 2020 at 97.

1978: Practical Electronic Flight Controls Are Introduced to Aircraft

The flight controls of an aircraft are the aircraft’s “brain.” They link inputs from the pilot to moveable parts of the aircraft, dictating how the plane climbs, banks, and descends. Original flight controls were mechanical constructs made of wires, rods, pulleys, and cables. Later versions of flight controls were augmented with hydraulics. These connected the flight stick and rudder pedals with control surfaces on the aircraft’s wings and tail. Thus, they allowed the pilot to maneuver the plane. However, even with hydraulics, these control systems had major flaws.

They were heavy and bulky, increasing the weight and size of the aircraft and making it slower and less fuel-efficient. Additionally, human reflexes are slow to recognize and respond to changes in flight conditions, even in the best circumstances. So, these systems also required a stable aircraft that defaulted to level flight after the pilot input anything.

Many engineers were working on developing electronic flight controls that would allow for faster, more precise inputs. NASA’s Digital Fly-By-Wire (DFWB) system wasn’t the first attempt at developing a computerized flight control system. However, it was one of the most influential in modern aviation. The organization tested computerized flight controls. They had equipped a rocket plane with a Honeywell MH-96 during the X-15 program. This created the adaptive flight control system (AFCS), which enhanced the plane’s handling. The enhanced handling was particularly helpful during atmospheric reentry. However, this system was never perfected or widely implemented.

More advancements to computerized flight systems came during the Gemini and Apollo programs. In 1969, the Lunar Module, piloted by Neil Armstrong during the Apollo 11 mission, used a digital, computer-driven fly-by-wire system. Finally, in 1978, an F-16 Fighting Falcon plane was converted to use electronic controls, and the rest is history.

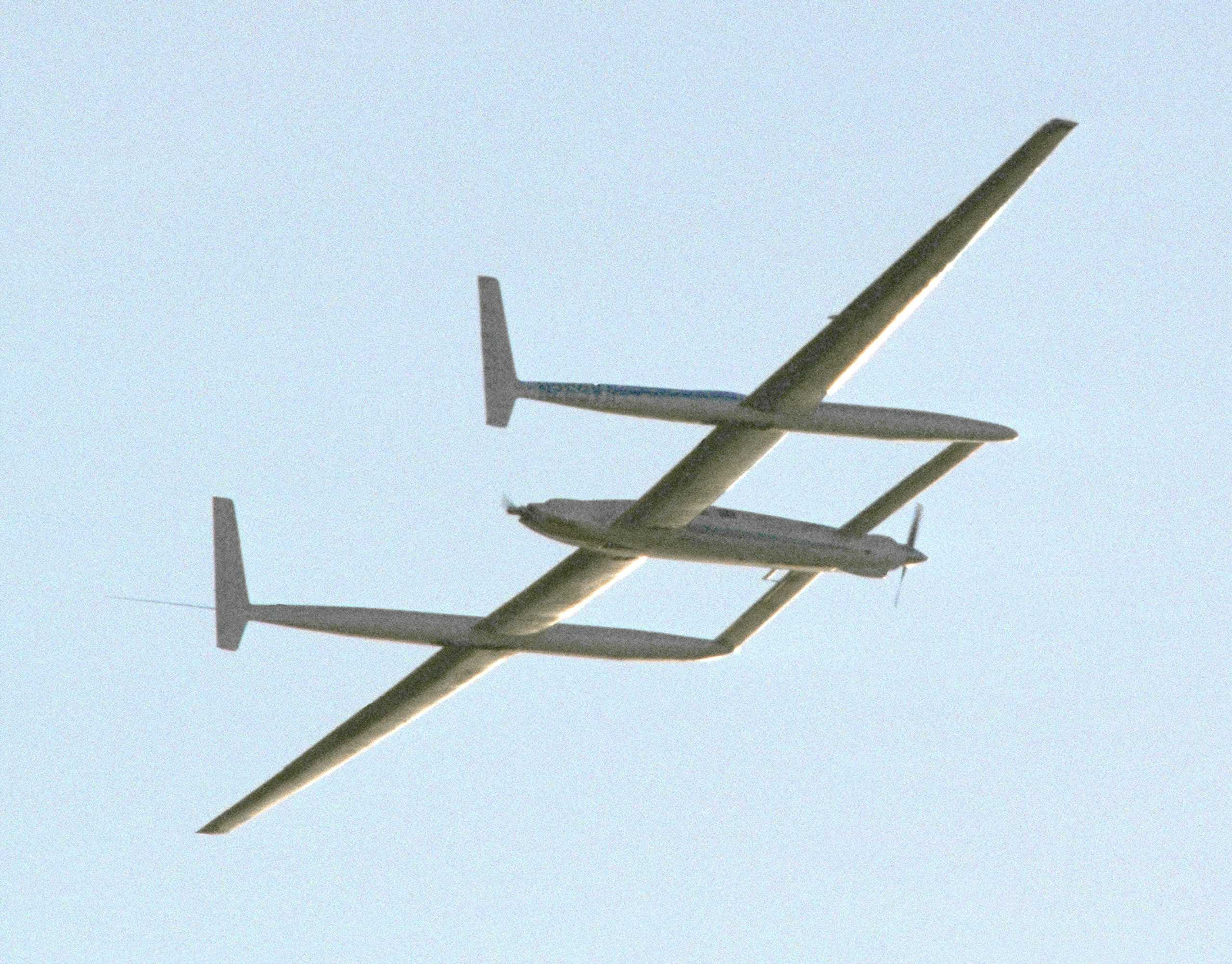

1986: First Nonstop Circumnavigation Occurs

The first nonstop flight around the world occurred in 1986. The Voyager aircraft was the one to do it. It was a unique feat of aviation that was essentially just a flying fuel tank. The aircraft was made primarily of plastic and stiffened paper to reduce the weight of the frame. Voyager was built by Burt Rutan of the Rutan Aircraft Company. Most people either didn’t think the trip was possible or didn’t care if the trip was possible. Thus, Rutan had virtually no external funding. No governments and few corporations were interested in the project. However, out of sheer passion and stubbornness, the Voyager was born in all of its plastic and paper glory.

The aircraft carried more than three times the weight of the frame in fuel. Every single possible space that could be used for storing fuel was used for exactly that. The body was made of layers of carbon fiber tape and paper impregnated with epoxy resin. It had a 111-foot wingspan and a horizontal stabilized on its nose, a trademark of Rutan designs. All modern tenets of aircraft design were forgone in favor of reducing the overall weight of the aircraft.

It was piloted by Burt’s brother, Dick, and Jeana Yeager (no relation to Chuck Yeager). They shared the controls. However, due to challenging weather conditions, the more experienced Dick controlled the plane for more of the duration. They brought a supply of food. However, both had weak stomachs in the air and barely ate. They each lost about 10 pounds each during the nine-day, four-minute flight. When the plane landed, it had just five gallons of fuel left. (Check out some NASA inventions that changed the world.)